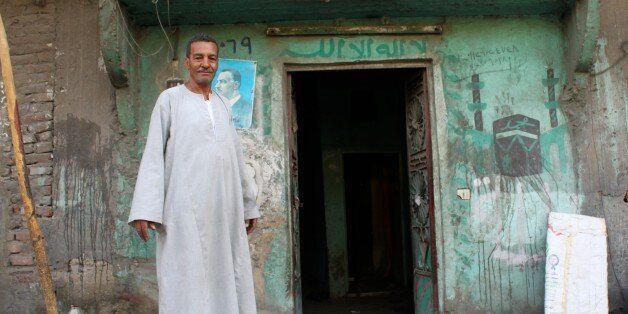

CAIRO — When Khaled Othman stands in front of his dilapidated house in the Duweiqa neighborhood of the capital’s sprawling Manshiet Nasser slum, he beams with pride.

Unlike many of the shacks that lack running water and electricity, Othman’s house of concrete and bricks has a water tap and intermittent power. The 45-year-old hard laborer turned small business owner considers himself lucky.

“My life’s work has been put into this house,” he said as his daughter-in-law, her face fully veiled in a niqab, held up a cell phone to light the hallway during a power outage. “I live well.”

Othman and many of his neighbors moved more than 30 years ago to this area, the poorest part of one of Cairo’s largest slums. After saving money for years, he now runs an aluminum workshop and employs a dozen people. But Othman and other residents say the government recently started destroying homes and buildings it deems unsafe, relocating people about an hour away. Large families are often split up and many people are forced to give up their jobs.

Othman’s daughter-in-law holds up her cell phone to light the hallway of her home during a power outage in Manshiet Nasser.

Othman’s daughter-in-law holds up her cell phone to light the hallway of her home during a power outage in Manshiet Nasser.

The demolition is a not-so-distant nightmare. In 2008, a landslide in Duweiqa killed more than 100 people and left scores of families homeless. As a result, the government leveled some of the surrounding houses and pinpointed 404 unsafe areas in greater Cairo. The project largely came to a halt when the 2011 revolution hit Egypt and the state collapsed, according to Yahia Shawkat, a housing rights officer at the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights, which works closely with Duweiqa residents. But now people’s homes are being demolished once again, and they are being forced to relocate.

“The state is back in action,” Shawkat said. “They are picking up where they left off.”

When the revolution first began more than three years ago, many Duweiqa residents took part in the mass protests that engulfed the country. They desperately hoped things in their neighborhood would change. But now, like many Egyptians living in informal housing, the people of Duweiqa tell the same story they’ve been telling for decades: They feel forgotten, used and afraid.

Shoeless children, some of whom have obvious skin infections, dig through garbage heaps, searching for things they can use or sell. Unemployed young men sit around in the crippling heat, the overwhelming smell of sewage hanging in the air. Women with babies perched on their hips peer out the windows of crumbling buildings. And the ruins of demolished homes serve as a constant reminder of what could come next for those who are left.

“There has been no change since the revolution,” 30-year-old Oma Mohamed said as Othman and dozens of other neighbors listened on, nodding in agreement. “People have given up hope that things will change. The injustice continues.”

While the government usually provides housing to the Duweiqa residents it evicts, the process has in some cases taken more than a year. Residents say their new homes are often not big enough for large families, forcing them to leave people behind. Parents complain that they either have to pull their children out of school or leave them in Duweiqa with friends or family until the school year is over.

“The government reaction is arbitrary and disappointing,” Shawkat said. “Money is being misspent. There are several current government housing projects underway and none of them adequately address the poor.”

A view of the Manshiet Nasser slum shows a government-built housing project towering above crumbling homes.

A view of the Manshiet Nasser slum shows a government-built housing project towering above crumbling homes.

In March, former military chief Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi, who is widely expected to win the upcoming presidential elections despite a massive crackdown on protesters and political dissidents, announced a five-year campaign to provide 1 million housing units to low-income Egyptian youth. But Shawkat argues that the term low-income doesn’t apply to people living in Duweiqa, many of whom say they only make about $7 a day. The housing units will initially cost roughly $1,400 to $2,140, with additional payments over the next 10 to 20 years, according to the Egyptian news site Mada Masr.

Duweiqa itself became the site of a government housing project in the late 1990s, and a handful of concrete structures, said to house thousands of people, now tower above the neighborhood’s other homes. But many residents say it has been nearly impossible to get a spot in the buildings, and rumors of bribery run rampant.

Residents fear that if they’re relocated, their whole lives will be uprooted, particularly their means of making money to support their families.

“There’s a community here,” said Heba Mahmoud Ahmed, a 48-year-old mother of 10 who has lived in Manshiet for 30 years. “But there, we can’t survive,” she said, referring to the neighborhoods where people are forced to move.

“We only want to feel safe,” a man standing behind her shouted, his frustration palpable.

Shawkat said that he fears the situation will remain unchanged after the presidential elections later this month, unless money is redirected toward housing Egypt’s poorest populations. But some residents express faint hope that perhaps things will be different under Sissi.

A woman pulls the curtains back to let light into her home in Manshiet Nasser.

A woman pulls the curtains back to let light into her home in Manshiet Nasser.

When asked who he is voting for in a few weeks, Othman doesn’t blink an eye: Sissi, of course, he says. But he’s not voting for Sissi because of the leader’s promise to restore security, a popular reason among Egyptians who are fed up with the daily bombings and years of turmoil. Othman dreams that Duweiqa will be restored: “We hope that Sissi will help us,” he said.

Others in the area are not as confident. “I haven’t made a decision yet,” a man who introduced himself as Hassan said in response to Othman. “I’ll vote for whoever has potential for the country.”

Othman’s livelihood — from his workshop to the chickens and goats living on his roof that feed his family — will depend on what the country’s next leader decides. He and his neighbors pray that Duweiqa will be spared.

As one resident simply put it: “May God fix things now.”

May Kamel contributed reporting from Cairo.