BEIJING –- President Barack Obama had barely finished shaking Chinese President Xi Jinping’s hand to seal this week’s landmark climate agreement before the predictable responses poured in from Washington. Congressional Republican leaders called the agreement “job-crushing” and part of the president’s “war on coal” that was “creating havoc” around the U.S. When Xi stepped from the rostrum, he faced no obstinate opposition party and virtually no public criticism of the agreement. That silence presents the image of a bureaucracy prepared to fall in line and spring into action, but “nothing could be further from the truth,” according to David Lampton, director of China studies at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies and author of a recent book on Chinese political leadership.

“The coal industry accounts for 60-plus percent of China’s energy, and entire provinces, cities, industries, and bureaucracies are economically dependent on this dirty energy source,” Lampton told The WorldPost in an email. “Interest groups in China don’t all welcome a fundamental restructuring of the energy economy any more than do analogous American groups.”

Smokestacks clutter the horizon in Longmen, Shaanxi, one of many cities in the region dependent on high-emission industries and coal mining. (Matjaž Tančič for The Huffington Post)Breaking through that opposition in the Chinese system requires a certain dose of raw political power, and recent moves by Xi on anti-corruption and economic restructuring suggest he may be concentrating enough strength in his own hands to begin bending the country’s long-term emissions curve. That political muscle is something that had been missing for much of the past decade. Xi’s predecessor, former president Hu Jintao, was often characterized as the “first among equals” in a politburo that prized consensus. While the system generated 10 years of hyper-fast growth, the price tag came in the form of environmental degradation and politics increasingly controlled by interest groups draped in powerful patronage networks, experts said.Leading state-owned oil companies influenced or simply ignored regulations on gasoline quality standards, mining officials got rich off legal and illegal coal mines, and mammoth infrastructure outlays spurred fast growth for state-owned cement and steel producers.

Smokestacks clutter the horizon in Longmen, Shaanxi, one of many cities in the region dependent on high-emission industries and coal mining. (Matjaž Tančič for The Huffington Post)Breaking through that opposition in the Chinese system requires a certain dose of raw political power, and recent moves by Xi on anti-corruption and economic restructuring suggest he may be concentrating enough strength in his own hands to begin bending the country’s long-term emissions curve. That political muscle is something that had been missing for much of the past decade. Xi’s predecessor, former president Hu Jintao, was often characterized as the “first among equals” in a politburo that prized consensus. While the system generated 10 years of hyper-fast growth, the price tag came in the form of environmental degradation and politics increasingly controlled by interest groups draped in powerful patronage networks, experts said.Leading state-owned oil companies influenced or simply ignored regulations on gasoline quality standards, mining officials got rich off legal and illegal coal mines, and mammoth infrastructure outlays spurred fast growth for state-owned cement and steel producers.  Experts contend that powerful state-owned energy companies and regional interest groups exerted heavy influence on environmental policy under the Hu administration. (Matjaž Tančič for The Huffington Post)

Experts contend that powerful state-owned energy companies and regional interest groups exerted heavy influence on environmental policy under the Hu administration. (Matjaž Tančič for The Huffington Post)

But meeting China’s newly announced pollution targets will require disrupting those clusters of power and the enormous amounts of energy they require to thrive. Li Shuo, a senior climate and energy campaigner with Greenpeace East Asia, said China’s goal of producing 20 percent of energy from renewables in 2030 will require Xi to restart long-stalled reforms.

“I cannot imagine we deliver this 20 percent target without doing a surgery on our electricity system,” Li said. “Reforms in electricity markets have been long awaited, but they sort of stopped in the early 2000s and we basically had a lost decade without anything being achieved.”

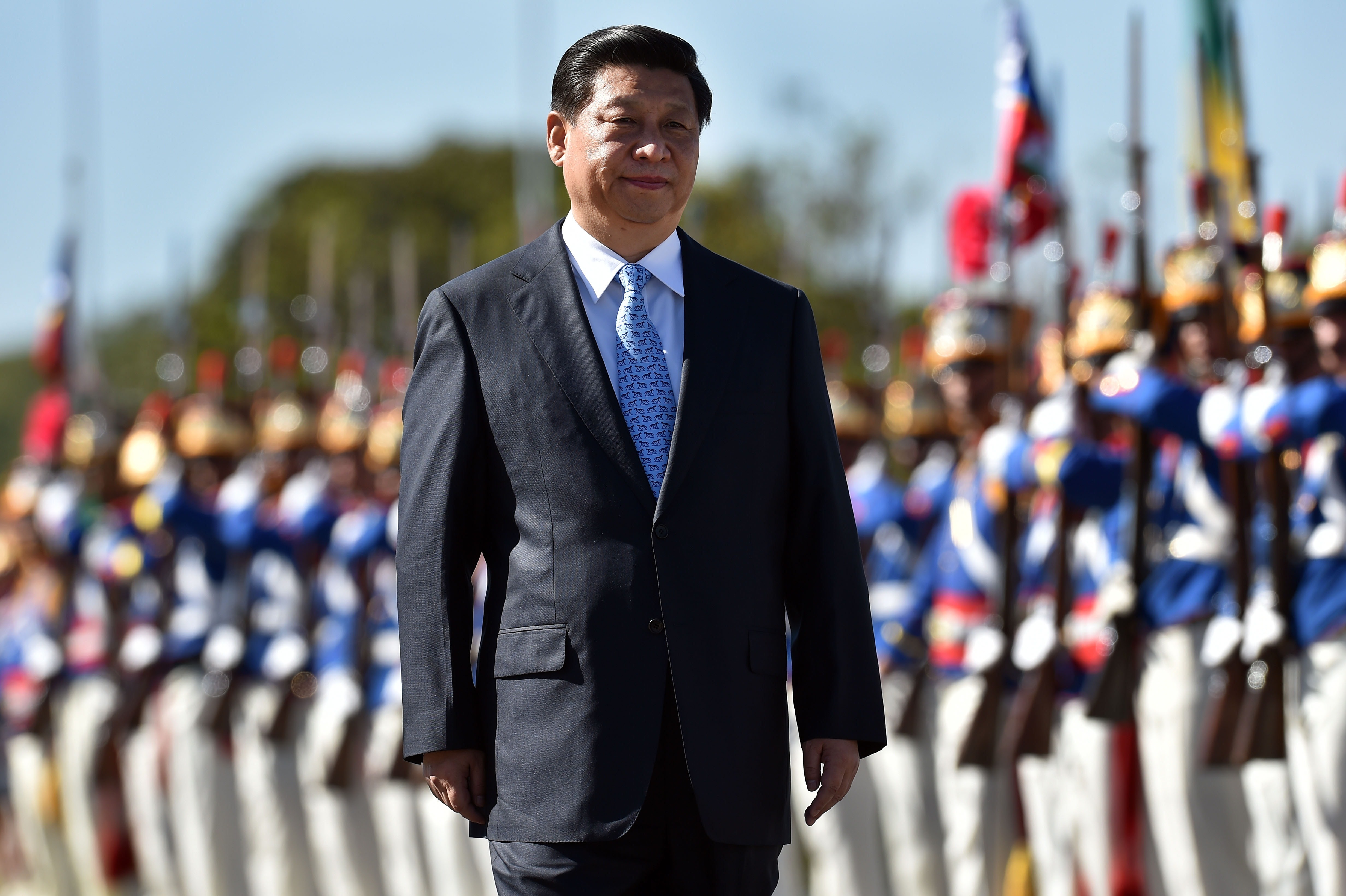

Xi, just two years into what will almost certainly be a 10-year stint as president, has already established himself as China’s most powerful leader since Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s. Critical to that power projection has been a fierce anti-corruption campaign in which Xi has vowed to take down both “tigers and flies” –- high-ranking officials once thought untouchable as well as low-ranking bureaucrats abusing their power.

“Xi is undisputedly the national leader at this point,” said Dali Yang, professor of political science at the University of Chicago. “There was a lot of eagerness to see a new generation of leaders take more decisive action for reform, and now they’ve got it.”

Xi Jinping has quickly consolidated power over China’s government apparatus. (NELSON ALMEIDA/AFP/Getty Images)

Xi Jinping has quickly consolidated power over China’s government apparatus. (NELSON ALMEIDA/AFP/Getty Images)

Whether by chance or design, Xi’s anti-corruption campaign has hit hardest in some of China’s largest oil and coal empires. Xi’s prize “tiger” appears to be Zhou Yongkang, a retired Politburo Standing Committee member and former head of PetroChina, the country’s largest oil company. Zhou is the highest-ranking official to come under investigation since the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949, and his sprawling corruption case has already ensnared several member’s of PetroChina’s top brass.

Another favorite punching bag of Xi’s has been the nexus of coal money and political power in central Shanxi province. Located in the heart of Chinese coal country, Shanxi has seen six current or former members of the province’s highest-ranking political body come under investigation, along with at least 17 lower-ranking officials.

Experts are quick to point out that investigations against Zhou Yongkang and others are deeply rooted in Xi’s personal consolidation of power — power that he has used to crack down on dissidents, human rights lawyers and even microbloggers. Paving the way for emissions reductions may not have been Xi’s original motive for going after Zhou and Shanxi coal tycoons, but experts said those moves have in the end strengthened him and handicapped likely opponents in battles over energy policy.

Zhou Yongkang is the highest-ranking official to come under corruption investigation since the founding of the People’s Republic of China. (Nelson Ching/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Zhou Yongkang is the highest-ranking official to come under corruption investigation since the founding of the People’s Republic of China. (Nelson Ching/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Professor Yang said aggressive anti-corruption moves have already begun to bear fruit: The Ministry of Environmental Protection and local governments are having greater success leveling sanctions against polluters, and critical media coverage of energy giants is finding greater expression in popular media.

“I won’t say it’s a transformation, but it’s certainly a way in which environmental regulation has begun to be applied with more vigor to the major state-owned enterprises,” Yang told The WorldPost.

Interest group squabbling aside, Xi will be pressing on an open door with emissions reductions in two areas: Economic policy and public opinion. China’s long-term emissions trends are largely dictated by economic structure, and analysts see major environmental dividends if Xi can push through a long-awaited economic rebalancing plan.

“China is trying very hard to change the structure of the economy so it’s not continuing to rely on heavy industrialization and investment,” said Wang Tao, a researcher on energy issues at the Carnegie-Tsinghua Center for Public Policy. “That will change the landscape of China’s environmental issues.”

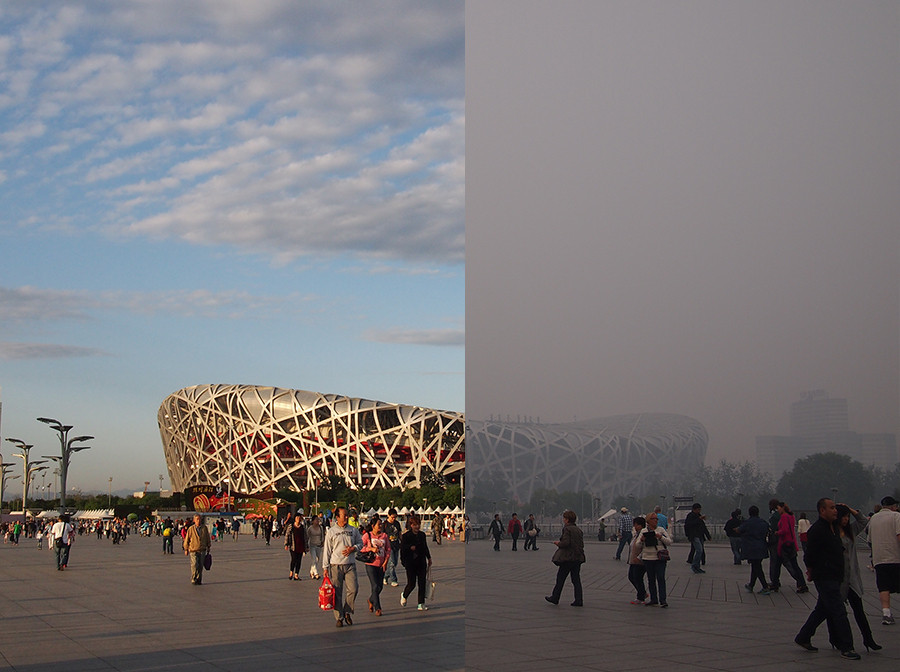

Pictures taken at Beijing’s National Stadium under clear skies and heavy smog. (Jeffrey Kessler for The Huffington Post)

Pictures taken at Beijing’s National Stadium under clear skies and heavy smog. (Jeffrey Kessler for The Huffington Post)

That transition has likely contributed to this year’s decline in coal consumption, the first such dip in well over a decade.. If that trend continues, Xi also may enjoy major public support from urban citizens who have grown increasingly angry over smog-choked skies. Local pollution and global warming are two separate issues, but both are aggravated by China’s decade-long love affair with coal, and the government may score points at home and abroad by slowly shrinking coal’s role in energy systems.

Despite Xi’s public pledges, his political strength and the economic forces already slowing emissions growth, the project may very easily fail. Oil and coal interests could reassert themselves in twisting energy policy, or economic disruptions could scare leaders into once again splurging on an infrastructure stimulus program. But even with the possibility of retrenchment, the calculus on what’s possible in China’s climate policy appears to have shifted.

“It’s a bit hard to imagine this happening even just two or three years ago -– things have come a long way,” said Li of Greenpeace. “My personal view is that we’re seeing more political stuff than environmental stuff, but if you engage in those forces, you know how difficult it is sometimes. I do have my sympathy, and I think this should really be the trigger of things.”