Nathan Gardels is the editor-in-chief of Noema Magazine. He is also the co-founder of and a senior adviser to the Berggruen Institute.

California’s state of mind, as much as its magnificent landscape, has always loomed large in the global imagination. And just when many were beginning to believe that the future of the Golden State had passed it by, California is breaking new ground again on many fronts.

California has long moved on from its clichés. We’ve gone from the hula hoop to the Hyperloop; from Midwestern migrants looking for opportunity in the sun to Latinos reaching for the middle class; from the military-industrial complex to the planet’s digital network platform. Gov. Jerry Brown, once maligned as Governor Moonbeam, is arguably the most grounded politician in America today, responsibly rising to meet the challenge of expectations diminished by natural and fiscal constraints.

It is not so much each of these shifts on its own, but in their conjunction, that California is leading the way once again. These conjoined developments will redefine the California Dream and, in turn, widely impact how others approach their future.

Here are the three areas of transformation that matter most:

Climate change and governance.

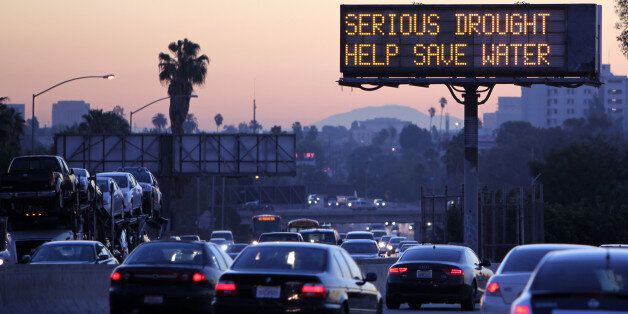

Brown, an early apostle of ecology whose past administrations have done much to clean up air pollution as well as boost fuel efficiency and energy-saving appliance standards, has his feet firmly planted in the state’s parched earth. Peering down the road with alarm, he sees “the shadow our future throws,” as his friend and mentor Ivan Illich once put it. Brown simply says of drought and climate change that “we have to see it as it is” and adapt accordingly.

The fullness of time and the scarcity of water have matured Brown and his famous “era of limits” philosophy from the 1970s. By imposing mandatory limits on water use and announcing the most aggressive effort to cut carbon gas emissions in the country, Brown has busted the bubble of collective denial of everyone with a yard, a walnut orchard or an SUV who assumed boundless resources and the limitless capacity of nature to absorb the exhaust of industrialized desire.

Desiccated reservoirs, frequent and fierce wildfires, defrosted mountain peaks and brown lawns are lodged now in our awareness, a jarring contrast to that iconic image of suburban sprawl with swimming pools Ronald Reagan once so proudly showed Mikhail Gorbachev on a visit to California.

What is encouraging is that this shift in awareness was brought about by intelligent governance. Brown, the enfant terrible of the 1970s, has turned out to be the grown up in the room. Pronouncing that “fiscal responsibility is the predicate of democracy, not its enemy” he quickly balanced the budget, first through painful cuts and then a temporary tax increase. He further persuaded the public to approve the paradoxically named “Rainy Day Fund” as a reserve for fiscal emergencies. The governor’s hallmark disposition of frugality as the wise use of fiscal and natural resources is — for now — stamped on Sacramento.

By imposing restraint on water use, greenhouse gas emissions and the budget, Brown has done the hardest — but most essential — thing in democratic political life: He has looked beyond the short-term horizon of immediate constituency pressures and the next election cycle to make tough decisions for the long-term good of the state.

“Rising to meet diminished expectations checked by natural and fiscal constraints is the mark of responsible leadership.”

What makes Brown stand out is that he has simply done what is necessary — a rare feat in the dysfunctional politics of today’s democracies where pandering to organized interests and kicking the can down the road is the norm. His stewardship will be the benchmark for future leadership.

A technological renaissance.

In California, limits don’t stifle innovation but stimulate it. And California’s hi-tech community is the ready and able incubator and midwife to take up the challenge.

In the same way Brown has taken on climate change through political regulation, Elon Musk has taken it on with technological innovation. His electric Tesla and ever-more durable batteries for storing energy chart the path toward the renewable energy infrastructure of the future.

We all know about how Apple, Facebook, Google, Twitter, Instagram and Snapchat have transformed the way we communicate with each other. But what is most promising is the convergence of exponential technologies from artificial intelligence, 3-D manufacturing, infinite networks, the “Internet of things,” regenerative medicine and biogenetics being born and developed in California today.

In Silicon Valley, Peter Diamandis and Ray Kurzweil have put it all together at their Singularity University. They grasp better than anyone how the convergence of this array of technologies can create entirely new possibilities of health, well-being and abundance.

Craig Venter, the pioneering cartographer of the human genome, is combining the computing power and falling costs of Big Data analysis with biology at his labs in La Jolla in order to read and write genetic code.

Fifteen years ago it cost $100 million to map a person’s genome; now it costs $1,500. By learning to read and write genetic code, Venter and his colleagues will one day be able to correct defective genes that cause disease, rapidly decipher viruses, manufacture vaccines and turn carbon emissions into fuel.

“California has become like a gigantic Renaissance Florence for the knowledge and tech-driven economy shaping the whole world.”

“Silicon Valley” is often used as the shorthand for labeling innovation in California. In truth, vibrant cross-pollination is happening across the state. California has become like a gigantic Renaissance Florence for the knowledge and tech-driven economy shaping the whole world.

Tax policy and new constituencies.

California will soon become the first minority majority state, with non-whites, mainly Latinos and Asians, outnumbering whites. In 2014, Latinos became the largest single ethnic group in the state, comprising 40 percent of the population.

This new demographic reality will redefine the California Dream no less than the scarcity of water, the lifestyle changes dictated by climate change and the benefits of tech revolution.

Above all, it will likely be felt in tax and spending policies. The Proposition 13 property tax revolt of 1978 still defines the fiscal framework of California. That revolt was sustained largely by an older, white middle class reasonably, at the time, seeking to protect their assets from a bloating state. The political constituency of California’s future, however — which is largely Latino, Asian and youthful — is seeking to build their assets through upward mobility.

That changes the equation. For aspirational constituencies striving to reach the middle class the most important thing is an opportunity web and trampoline to boost their chances in life.

“For aspirational constituencies striving to reach the middle class the most important thing is an opportunity web and trampoline to boost their chances in life.”

Even though California has one of the most progressive tax structures in the nation, inequality is rising and dashing aspirational hopes. Something more is needed as USC Professor Edward Kleinbard has articulated and former assembly speaker, now senator, Bob Hertzberg, has sponsored in legislation: namely, a new philosophy of governance that focuses on the overall progressive outcome that can be achieved through modernizing the tax code and investing in infrastructure and public higher education — the key means of upward mobility. Such investments are inherently progressive in the distribution of their benefits and in the creation of new well-paying jobs.

Investment requires adequate resources. California’s $2 trillion economy has shifted from being mainly agricultural and manufacturing in the 1950s and 1960s, when the framework of today’s tax system was set up, to one based on information and services, which now account for 80 percent of all economic activities in the state. Yet, the service economy in California is not taxed at all. If you buy a donut in a coffee shop, you pay a sales tax on goods. But if you buy a legal, financial or entertainment service you are not taxed.

A tax system that responds to the aspirations of the new constituencies must sensibly be based on this real economy of the 21st century while ensuring that new revenue is invested in strengthening the ladder of mobility. That means, as Hertzberg has proposed based on the original recommendations of the Think Long Committee for California, rebalancing the fiscal formula by reducing income taxes across the board in a way that favors the middle class and small entrepreneurs while extending a sales tax on services.

In April, the state’s Board of Equalization issued a report that concluded taxing California’s service sector would generate as much as $122 billion in revenues, an amount greater than the entire general fund budget at present. After exempting sizable key areas such as education, health care and small businesses from any new tax (80 percent of California companies have less than 10 employees), Hertzberg expects to reap $10 billion annually in new revenues.

For the moment, the lobbyists of the status quo are lining up against Hertzberg’s measure, Senate Bill 8, as would be expected. But sooner or later a policy that is wholly in the interests of the state’s rising new constituencies will win out. Just as with water and climate change, the guardians of the past will have to face reality, “see it as it is” and adapt.

Together these transformations constitute a new state of mind fully capable of building a future for California as promising as its past.

This article also appears in the Sacramento Bee.