Nathan Gardels is the editor-in-chief of Noema Magazine. He is also the co-founder of and a senior adviser to the Berggruen Institute.

In his 2011 book, “Civilization: The West and the Rest,” historian Niall Ferguson credits a series of “killer apps” for enabling the West to take off in the 15th century and remain dominant for the next 500 years while the rest of the world stalled. The two leading “apps” in his scheme were competition and science.

In that book, Ferguson recounts how competition among the nations and city-states of Europe over exploring trade routes to the New World and later, over exploiting the cutting-edge discoveries of the Newtonian scientific revolution, propelled them all forward. Each drove the others to greater heights of development.

A similar dynamic is taking place in Asia today. The fear of being left behind under the shadow of China’s ascent is stoking competitive ambitions across the region. The Middle Kingdom’s efforts to make its mark in every realm — from outer space to artificial intelligence and sustainable environmental practices — incites others in its neighborhood, and indeed in America and Europe as well, to do likewise.

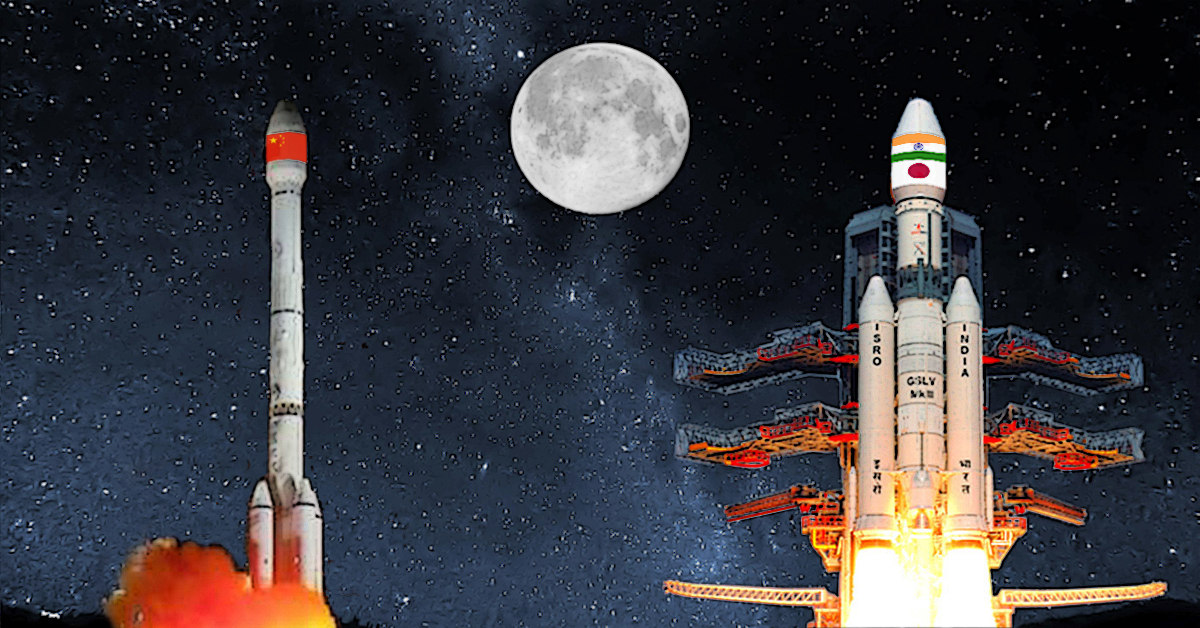

Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan describes how geopolitical anxieties in Asia have prompted the governments of India and Japan to join together in a new project to land on the moon.

“The recent launch of the SpaceX rocket Falcon Heavy is a good illustration of the entry of efficient and innovative private players into an arena long considered the preserve of national governments,” she writes from New Delhi. “But this does not mean that national competition in outer space is disappearing. If anything, it is actually accelerating in Asia. China’s growing space prowess is leading to a space race with India and Japan, which are beginning to pool their resources to better match Beijing.”

She goes on to say: “Both are acutely aware of what China has accomplished, with four moon missions between 2007 and 2014 alone. China’s technological dominance weighs on the Asian strategic balance, and both India and Japan are clearly feeling the pressure.”

Chandran Nair notes how a new sustainable practice implemented by China is setting off a global competition in waste recycling. “Beijing decided to halt imports of plastic waste in January, which had a knock-on effect on the rest of the world, since China has been a major outlet for recycling trash. Since then, both the European Union and the U.K. have announced their own controls on plastics and plastic waste,” he writes from Hong Kong.

These government decisions, in turn, prompted several major multinational companies from Coca-Cola to Walmart to pledge in Davos last month to reduce their use of plastics. Drawing on the compelling card of global competition, Nair proposes that the Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba lead the way in regulating the use of plastics in packaged deliveries, thus pressuring the other global giant, Amazon, to follow suit.

Even as China’s juggernaut spurs competitors, the contradictions within its future vision could well cause its own ambitions to stumble. In domestic policy, China’s “Internet plus” policy — a long-range plan to link cyber and physical infrastructure through high-tech innovation and the “Internet of things” — runs up against what might be called the “Internet minus” policy of censorship, which impedes a pragmatic approach to addressing its challenges through seeking truth from fact. Innovation entails steady disruption while the Communist Party, above all, seeks stability and control.

To the extent China tries to extend control over inflows of information — including by seeking to curtail critical content in scholarly journals from the West that circulate in Chinese academia — or tries ham-handedly to promote its own narrative in the Western media, it is hurting its own cause. As Thomas Kellogg writes, such an effort has already been saddled with a pejorative moniker — “sharp power.” Yet, there is an important distinction between China and Russia’s efforts to manipulate public opinion. Russia is trying to sow division and discord in the Western body politic to undermine the democratic discourse; China is clumsily trying to control its own image in the West.

Jonathan Hillman notes a related conundrum in China’s main foreign policy initiative. “An idea as big as China’s ‘Belt and Road’ is bound to have contradictions. As Chinese President Xi Jinping’s signature foreign policy vision, it is massive in all dimensions, aiming to bind Beijing with the rest of the world through more than $1 trillion of new infrastructure, scores of trade agreements and countless other connections,” he writes from Tashkurgan, a Chinese town on the Pakistan border.

“But there is a fundamental tension between the connectivity China says it seeks and the control it is unwilling to give up,” says Hillman, referring to the massive presence of anti-terror security forces and imposing police outposts across Xinjiang’s predominantly Muslim Uyghur towns and cities. “Even as China claims to be championing globalization and broadening ties, it is clamping down in critical borderlands that Belt and Road routes would pass through, potentially crippling its own projects,” concludes Hillman.

One clear lesson of history is that the growing dominance of a major power like China will generate challengers in kind, both those driven to compete as well as those determined to resist.

This was produced by The WorldPost, a partnership of the Berggruen Institute and The Washington Post.