Denise Hruby is a freelance journalist who was based in China from 2015 to 2018.

JUBA, South Sudan — The fact that South Sudan has a petroleum ministry speaks to oil’s role in the economy — 98 percent of the government’s budget comes from exporting it. The ministry’s compound is protected by a high concrete wall; on its exterior, a sign pledges “to turn our independence into the welfare of society and development.” Perhaps more tellingly, the wall is riddled with bullet holes.

While oil hasn’t been the root cause of South Sudan’s main conflicts, it has exacerbated and fueled fighting and suffering.

And oil sets the agenda when it comes to the international community’s response to the country’s crises. It even got China to deviate from its customary policy of non-interference in other countries’ affairs. The state-run China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) owns a 40 percent stake in South Sudan’s biggest oil fields and has invested billions in oil-related infrastructure. Briefly, the rising superpower looked like it would be a leader in helping end the conflict. Now after five years, a peace deal seems within reach, but China won’t be taking any credit for it.

For decades, Beijing refrained from meddling with sovereign nations’ internal affairs. As long as economic ties flourished, it would turn a blind eye to human rights abuses and corruption. But with increasing investments abroad comes more clout, and as the United States scales back its international commitments, China is emerging as an obvious development partner.

For that to work, Beijing’s foreign policy would need to be an antidote to America’s — a balancing act between flexing its muscles and being a less meddlesome alternative.

In the 1990s, Western countries abandoned what is now South Sudan’s oil fields, judging them too risky; in 1996, these became one of the CNPC’s first investments abroad. China needed to secure its own energy needs, and at the time, South Sudan’s oil offered one of its few chances to do so. Now however, its role is one of legacy and prestige. Even if the oil fields were operational, less than 5 percent of China’s imports would stem from South Sudan — a negligible amount compared with those from Russia and the Middle East.

For South Sudan, however, China’s role was pivotal. It became a major benefactor, with bilateral trade reaching more than $2.5 billion in 2013 and investments at times surpassing those the nation made through oil exports. Thousands of Chinese businessmen had poured money into the new nation, so much so that as a Chinese grocery store owner told The WorldPost in April, the new capital of Juba started to see its first traffic jams. Juba was hoping for billions more and was counting on China to build an oil pipeline that would have made its exports independent from Sudan.

Then just two years after South Sudan’s 2011 independence, civil war broke out between the president, Salva Kiir, who belongs to the Dinka ethnic group, and his vice president, Riek Machar, who belongs to the Nuer ethnic group. Amid mass killings along ethnic lines, China took a stance by suspending weapons shipments worth millions of dollars. Beijing made it clear that it wasn’t willing to become a witness to what some nations, including the United Kingdom, have since referred to as genocide.

Carefully weighing how best to wield its economic leverage, Beijing reduced its oil investments. The political situation was so bad, it was hard to see how it could worsen. A new approach seemed possible without much risk, and so Beijing slipped into the role of peacebuilder. South Sudan would be a “new chapter for the Chinese foreign affairs,” said Zhong Jianhua, the country’s special representative on African affairs.

While Beijing didn’t care who won, the billions South Sudan was hoping for now had one string attached: stability. Behind the scenes, Chinese diplomats became key players in facilitating a 2015 deal to cease fighting and establish a transitional government. Economic growth and stability was as imperative for South Sudan, as it was for China, and Chinese diplomats thought dangling new investments as a carrot would work. But in a situation that echoes Western peace brokers elsewhere, China underestimated the complexity of the conflict and the deeply rooted distrust between warring parties.

Just a few months after the deal was reached, rebels took over the oil fields. Mass atrocities ensued. Tens of thousands were killed, and more than a million became refugees, helping make South Sudan home to the biggest refugee crisis in Africa today.

Beijing had wielded its leverage too lightly. From the beginning, as Casie Copeland, a senior South Sudan analyst for the International Crisis Group, told me, China’s “interest was in the oil fields and not necessarily in ending the conflict.”

Although it could have fully leveraged its clout with little risk to its own economy, Beijing quickly took the backseat. African problems, Beijing said, need African solutions, and thus it defers to the African Union and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development, which have become the conflict’s main mediators. Just this month, for example, China’s representative to the United Nations said it was following the African mediators’ lead when it abstained from voting on an arms embargo.

This summer, negotiations between the warring parties moved forward toward a peace deal that would establish a “permanent” ceasefire and a new government helmed by President Kiir. Whether it will bring real peace is uncertain, but looking back at China’s involvement, it is clear that South Sudan can only serve Beijing as a lesson in foreign policy: If it wants to lead, then only bold steps lead to bold results.

So far however, a timid approach has remained Beijing’s foreign policy norm, including with North Korea, where China wields significant influence, and with Myanmar, where China has helped broker talks between the government and rebel groups.

In South Sudan, this has caused palpable frustration. When I visited in April, ministries and officials that used to be accessible to journalists declined to comment. The Chinese embassy declined comment over the phone as well.

The China National Petroleum Corporation had moved from its previous location, but nobody seemed to know where. We found it behind a thick, three-meter-high wall without any signage. Security guards briefly entertained me, curious about the European speaking some Chinese. If I could go to Sudan, they said, my chances for an interview would be slightly higher — all higher-ranking officials had moved to the Sudanese capital Khartoum.

That neither side was willing to talk to journalists “tells you a lot,” an analyst who has spent several years focusing on South Sudan told me. “Before, they were quite eager to communicate, because at least the investments were one positive thing they could talk about. And now, it seems they got nothing good to say about each other anymore.”

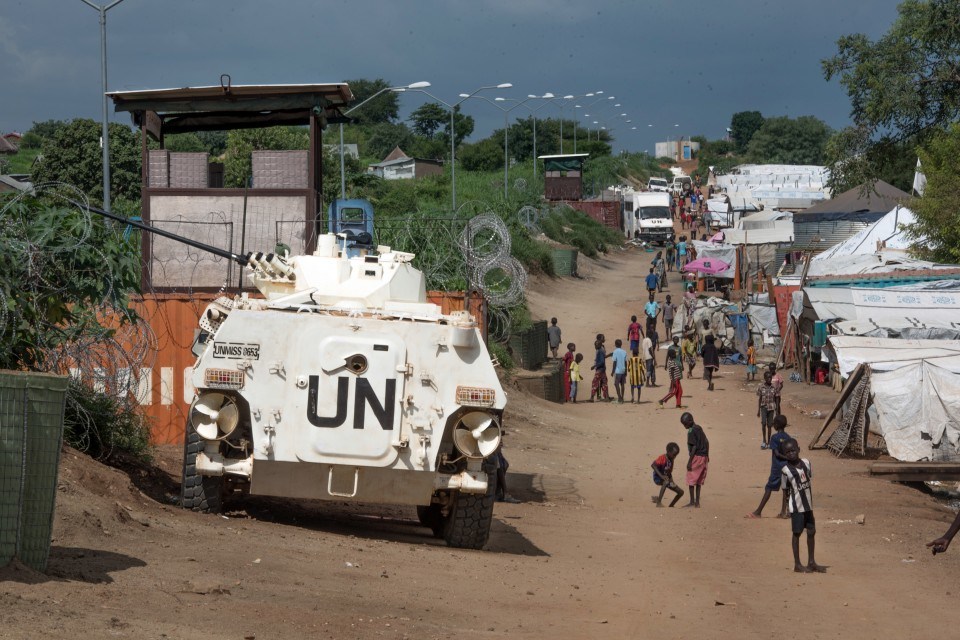

From China’s point of view, it is still supporting humanitarian affairs in South Sudan — the construction of a new hospital wing, China’s largest contingent of U.N. peacekeeping troops and substantial aid. But that hasn’t alleviated the discernible anger locals feel over China’s failure to fully throw its weight behind peace.

One man from Unity state, where China has some of its biggest oil investments, said that he used to drive his white Toyota pickup truck around his cattle farm and every once in a while, see a Chinese worker. “We don’t understand what they are doing, why they still want the oil,” he said. He now lives in a camp for those displaced by the war, surrounded by razor wire, and struggles to feed his three children. “Look around here: The people are dying. How can they care about the oil?”

This was produced by The WorldPost, a partnership of the Berggruen Institute and The Washington Post, and supported by a fellowship from the International Women’s Media Foundation.