Nathan Gardels is the editor-in-chief of Noema Magazine. He is also the co-founder of and a senior adviser to the Berggruen Institute.

In his recent book, “How Democracy Ends,” the Cambridge scholar David Runciman doubts that democracies can effectively battle oncoming challenges that have not yet fully arrived. “Climate change,” he writes, “lacks political grip on our imaginations because it is so incremental. The environmental apocalypse is only ever a creeping catastrophe. We experience it as a rumor.”

In other words, the future, by definition, has no present political constituency in systems legitimated by consent of the governed. In this sense, democratic politics can disable the requisite will to act until climate calamity is already upon us. That will likely be too late.

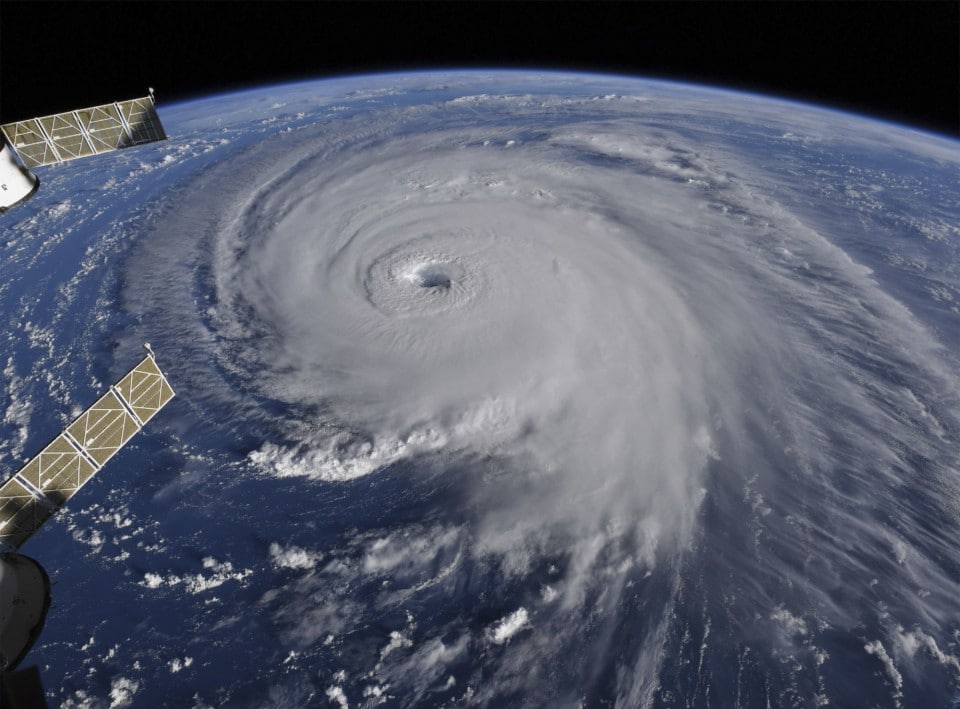

Ominous signs, such as intense storms like Hurricane Florence or this season’s wildfires, from California to the forests above the Arctic Circle in Sweden, are hopefully bringing forward a concrete awareness of what the future holds. Yet, as Barack Obama reminded Americans last week — referring to President Trump’s rollback on a wide range of policies, including on the environment — progress does not advance in a straight line. Two steps forward often entail one step back, the former president lamented. This is particularly true in democracies where partisan fever is so high that a new election can result in totally overturning a course of action that the public embraced only a few years earlier.

But there is no time to waste. As the Global Commission on the Economy and Climate recently reported, we are facing “a unique ‘use it or lose it’ moment.” If the world cannot reach the goal of the Paris climate accord to keep the global average temperature below 2 degrees Celsius in the next decade, the planet will heat up past the point of no return.

In short, when it comes to climate change, time is an ethical dimension. Whether our species can regain the time lost during this “one step back” is the open question upon which our ability to radically adapt, or even survive, depends.

In this respect, China’s one-party, long-term-oriented system presents yet another challenge to the West. Indeed, California Governor Jerry Brown warned this week that by sabotaging America’s electric car industry, Trump was handing the future of auto manufacturing to the modernizing Middle Kingdom, which is vigorously pursuing new battery technologies. China’s leaders believe in science. They have the will and capacity to take decisive and meaningful climate action on a large scale, without a break in the continuity of governance. Whether democracies can similarly rise to this challenge without resorting to authoritarian means will determine if, one dire day, the choice comes down to liberty or survival.

In The WorldPost this week, we publish varying perspectives on this challenge in tandem with the Global Climate Action Summit taking place in San Francisco, co-chaired by Governor Brown, former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg and China’s top climate negotiator, Xie Zhenhua.

Christiana Figueres, who presided over the successful negotiations that led to the Paris climate accord, focuses on particulate pollutants in the air that are the consequence of our civilization’s carbon exhaust. “Global warming is not just manifesting in devastating fires, floods and heatwaves; its causes are impacting nearly every breath we take,” she writes. “Thick, heavy smog caused by the burning of fossil fuels and crops is choking cities around the world. China has been forced to close tens of thousands of factories to reduce its air pollution. Air pollution in Africa has been ruled responsible for more deaths than unsanitary water or malnutrition. Last November, Arvind Kejriwal, chief minister of India’s capital city, wrote: ‘Delhi has become a gas chamber.’”

Figueres, however, is optimistic that we are on the cusp of a shift. “Driven in part by the demand for and the undeniable benefits of clean, breathable air, the paradigm in which development and economic growth depend on coal in particular is rapidly being replaced,” she writes. “The truth is that addressing global warming and its causes is now the only real way to secure economic growth. That means powering it with clean, everlasting, abundant alternatives. Governments everywhere can reap enormous benefits, including saving billions of dollars on healthcare, by fostering a shift to electric transport, eliminating fossil fuel subsidies and scaling ecosystem restoration including mangroves, peat bogs and forests.”

Erik Hoffner agrees on this last point. While carbon sequestration technologies are promising, he says, they are likely prohibitively expensive. The same result can be accomplished by the low-tech and far less capital-intensive alternative of agroforestry, which is “essentially a forest-mimicking agriculture that involves growing trees, shrubs and vegetables in tight assemblages.”

James Redford and Adam Browning argue that what unites Americans on climate action is, ultimately, the jobs and an improved economy that clean energy can bring. In a short video, they report from their road trip through Minnesota on local communities that are building a solar-based energy grid in this northern state not known for its sunshine.

Ali Hasanbeigi and Daniel Moran ponder an entirely new aspect in the climate change debate. While the Paris accord is based on measuring domestic emissions within a country’s borders, it does not count “emissions associated with the products countries import — which can often constitute significant shares of a nation’s economic activity.”

As a result, “more than 25 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions are embodied in trade and flow through this glaring ‘carbon loophole,’ one of the most critical and under-discussed problems in international climate policy circles.” To close the carbon loophole, the authors call on nations and companies to “buy clean” by establishing “rules that favor the purchase of cleaner, low-carbon products and that drive clean innovation through the power of the purse.”

One of the essential elements in fighting climate change is putting a worldwide price on carbon. To move toward this goal, I propose in my profile of Jerry Brown that he take on the role of a global elder statesman on the issue when he leaves office next year. He has not only made his state a leader in battling global warming; he has also strung together a global “network of the willing” to implement the Paris accord despite America’s official withdrawal. First and foremost among his tasks would be to integrate California’s sizable carbon trading market created by its “cap-and-trade” programs with similar markets in China and Europe.

“The model for Brown’s elder statesman role,” I write, “is Jean Monnet, a former French official and diplomat who devised the idea of the European Coal and Steel Community implemented in the 1950s. The driving notion was that regional integration of heavy industry in the Ruhr Valley along the French-German border in the years following World War II would accelerate economic reconstruction and make war ‘not only unthinkable but materially impossible.’”

Similarly, I argue, “the integration of cap-and-trade markets today would not only ultimately establish a global carbon price that would diminish reliance on fossil fuels; it would also create a bridge of common intent across boundaries to save the planet despite national conflicts arising today in trade and security matters. Tying our climate fates together would in effect serve as a kind of preemptive version of the Coal and Steel Community.”

This was produced by The WorldPost, a partnership of the Berggruen Institute and The Washington Post.