TIANMU VILLAGE, Tianjin, China — Since his rise to power, Chinese President Xi Jinping has waged a sweeping anti-corruption campaign that has targeted both decadent high officials and small-time tyrants — in his words, both “ tigers and flies.” For over two years, Xi has wielded the cudgel of corruption charges to decimate his political enemies and dethrone powerful leaders once thought untouchable.

But what happens when ordinary Chinese citizens join the anti-corruption fight?

Here in Tianmu Village outside the northern metropolis of Tianjin, hundreds of villagers are staging daily protests demanding that anti-corruption investigators swat at a man they accuse of being one of Xi’s “flies”: Communist Party Secretary Mu Xiangyou. For weeks, citizens in the predominantly Muslim village have gathered in front of the local government headquarters, holding up banners and making speeches accusing Mu of selling off village land and pocketing the profits.

Public protest represents a desperate attempt by villagers to grab the attention of anti-corruption watchdogs from the central government. But it’s also a strategy that is more likely to land the protesters in jail than Mu himself.

Even while the Xi administration has pushed sweeping reforms and waged a nearly unprecedented anti-corruption campaign, government officials have remained deeply hostile to any grassroots challenge to the status quo.

That simultaneous push for both deep reforms and absolute adherence to the party line has framed some deeply ironic juxtapositions: Last week, China’s legislature advanced the country’s first law on domestic violence, but just days later, Chinese police arrested feminist activists who have protested against domestic violence. In recent years, lawyers advocating public disclosure of officials’ assets have found themselves in prison on charges of “picking quarrels and provoking troubles.”

“[Xi] wants everything done by the party and through the party,” Bruce Dickson, a professor of political science at George Washington University, told The WorldPost. “For people deciding whether or not to engage in the protest, there are examples of protests being successful but also examples of people getting beat up or thrown in jail. It creates really contradictory signals.”

Critics have also argued that Xi’s corruption campaign has exclusively targeted political enemies, suggesting that it’s as much about consolidating Xi’s own grip on power as about systematically eradicating corruption.

Villagers protesting local corruption often stress their loyalty to the Communist Party, framing their demonstrations as appeals for higher officials to discipline local wrongdoers.

“Our Chairman Xi has gone and attacked the corrupt officials,” said one speaker in a video from the Tianmu protests. “Those of us here are heroes who have stood up to protect the correct line of the central party’s leadership! Anti-corruption actions — our actions — are patriotic, pro-party and just!”

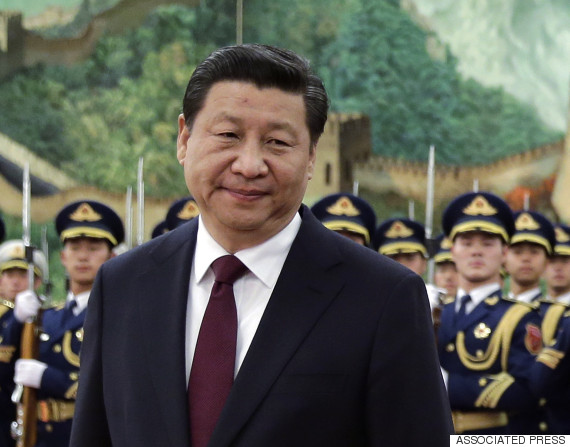

Chinese President Xi Jinping has launched a sweeping anti-corruption campaign.

Chinese President Xi Jinping has launched a sweeping anti-corruption campaign.

Residents of Tianmu village told Radio Free Asia, a media organization funded by the U.S. government agency Broadcasting Board of Governors, that Mu had accumulated vast wealth by selling off communal village land and pocketing the proceeds. Banners held up at the protests demand the village finances be opened up to public scrutiny.

In addition to serving as the local party boss, Mu is also a delegate to China’s National People’s Congress, which is currently holding its annual legislative session.

Public land sales in China are often deeply unpopular, but do not necessarily indicate corruption — many local governments strapped for revenue initiate land sales to spur development and pay off local debt. The WorldPost was unable to verify the villagers’ accusations against Mu.

When I arrived at the protests on the morning of March 6, several men — one of whom claimed to be from the Tianmu Village Committee, a governing body that works with Mu — surrounded me and attempted to push me away from the protests and into a car.

After demonstrators intervened, local police officers stepped in and demanded that I accompany them to the station to verify my credentials. But despite verification, I was still not allowed to return to the protests. At the police station, another self-identified member of the Village Committee said, “This is an internal village affair, and we’re going to handle it in the village.”

At least one local with whom I had communicated by phone was also detained at a police station that morning but released later that day.

Villagers gather in Tianmu Village to protest alleged corruption by village Party Secretary Mu Xiangyou.

Villagers gather in Tianmu Village to protest alleged corruption by village Party Secretary Mu Xiangyou.

The Chinese government has long said that it welcomes citizen participation in anti-corruption campaigns through the legal channels sanctioned by the party itself. But official complaints to the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, the party’s internal corruption watchdog, have historically proved ineffective. Huang Qi, a citizen activist who has tracked land-related disputes on 64tianwang.com for over 15 years, said that his data shows less than 1 percent of officially sanctioned corruption tipoffs are successful.

“Most people believe that you have to take up methods that officials don’t approve of: petitioning in Beijing, demonstrating, protesting,” said Huang, who has served two different multi-year stints in prison for his activism. “You have to generate some buzz.”

That buzz can be a very sharp double-edged sword for protesters and activists: Huang reports that five volunteers for his web site, which is blocked in China, have been detained in the past three months. But he said that the rhetoric emanating from Beijing has encouraged greater activism on land and corruption issues.

“There’s no doubt that the anti-corruption campaign that began when Xi took power has done a lot to jump-start anti-corruption activities by China’s farmers,” said Huang.

Despite the risks, villagers continuing to protest in Tianmu village are holding out hope that the central government would rather swat a “fly” than crush a village protest.

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story said that Radio Free Asia was funded by the U.S. State Department. It is funded by a government agency, the Broadcasting Board of Governors, but the agency is independent from the State Department.