KIRKUK, Iraq — They came without warning. Heavily armed and riding in hundreds of cars and Humvees stolen from the Iraqi army, the extremist Sunni fighters stopped outside a tiny farming village in northern Iraq and attacked the Shiite community there.

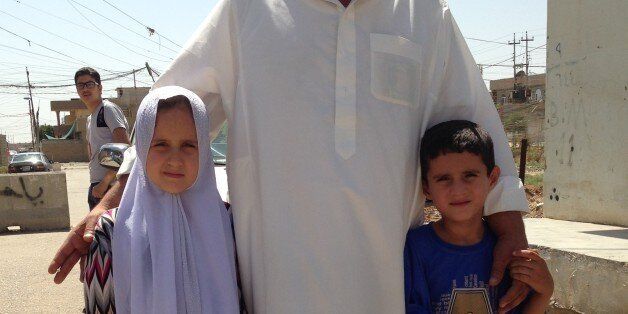

Hussein Khalil, among the hundreds who fled the village of Bashir last week, described the massacre from the relative safety of a Shiite mosque in Kirkuk, a city about 15 miles away. He was surrounded by dozens of Bashir residents, all members of the Turkmen ethnic minority, who nodded in grim approval of his account.

“We could barely flee,” said Khalil, his strong, sun-worn hands cradling his toddler son. “They burned houses and took the money. They killed people and then hung them in their homes.”

More than a dozen people were killed in the attack on Bashir that witnesses say was carried out by Sunni militants allied with the Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham, as well as Sunnis from neighboring communities. The account could not be independently verified, but the massacre in Bashir, as well as in three other villages, has also been recounted by other residents who fled the militants.

Explosions erupt on the horizon in Kirkuk on June 17 as Sunni extremist militants try to capture the Shiite Turkmen village of Bashir.

Explosions erupt on the horizon in Kirkuk on June 17 as Sunni extremist militants try to capture the Shiite Turkmen village of Bashir.

The attack comes two weeks after ISIS began wreaking havoc in northern Iraq, capturing the country’s second-largest city and executing Iraqi forces and unarmed civilians, many of them Shiite. The group has begun moving south toward the capital, with aims to create an Islamic caliphate stretching across Iraq, Syria and Lebanon. It views the Shiite members of the Turkmens — a minority group that also includes Sunnis — as heretical.

Khalil and his fellow residents of Bashir are sticking together, praying they can soon return to whatever is left of their home. Their biggest fear, apart from ISIS’s wrath, is the potential partitioning of Iraq into separate Sunni, Shiite and Kurdish areas. If their country does end up divided — an increasingly likely possibility as the government loses entire swaths of Iraq to Sunni fighters and Kurds alike — they could be displaced permanently. They refuse to accept that partition is the only answer to the relentless bloodshed, as many Sunni Muslims believe.

“We support a unified Iraq,” Khalil said, the group of men around him voicing their agreement. “We think it’s possible to live together.” One man, Jomaa Mohamed, interrupted him, exasperated: “We don’t know our future if the partition happens!”

For the Shiites seeking refuge in Kirkuk, a divided Iraq could force them from their homes, jobs and schools. And the Shiites who have long lived here wonder if they, too, will soon be on the run from Sunni fighters if Iraq splits apart.

“I want Iraq to stay united,” Yousif Taha, a Shiite resident of Kirkuk in his 20s, said by phone. “I believe in Iraq as a united country. For me the division into three separate states would be a disaster.”

Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, a Shiite, rejected the idea of forming a more inclusive government with Sunnis on Wednesday, despite pressure from the United States. Sunnis largely regard al-Maliki as a corrupt and alienating leader who fosters sectarian violence. In the southern capital of Baghdad, Sunnis are killed nearly every day now by Shiite militias who fear the advance of ISIS and its allies. Unlike the Shiites from Bashir, many Sunnis in the north welcome the idea of partition to break away from al-Maliki and his rule.

“I would support a partitioning of Iraq,” said a Sunni man named Mothana while walking in a central market, as a group of shoppers listened on intently. “It’s better if we rule ourselves. We’ve already gone back 2,000 years. Now there is so much bloodshed.”

However, he added, he does not support a Sunni uprising led by ISIS. “They’re trained in killing people,” he said.

Here in Kirkuk, a city with a heavy Kurdish population, many people are inclined to agree with Mothana’s views on partition. The city, long disputed by the Kurds and the Iraqi government, is now entirely controlled by Kurds, most of whom hope to break away from their semi-autonomous region into a truly independent Kurdistan.

Brig. Gen. Mohamed Rostam looks out from a military post in Kirkuk at what is now territory entirely controlled by ISIS.

Brig. Gen. Mohamed Rostam looks out from a military post in Kirkuk at what is now territory entirely controlled by ISIS.

“Of course, if things go in this direction, Iraq will be divided into three,” said Brig. Gen. Mohamed Rostam, a leader of Kurdish forces who now defend Kirkuk, as he sat in a military compound outside the city during last week’s attack on Bashir. His phone rang off the hook with people frantically pleading him to send his men to fight the Sunni extremists. “If ISIS goes there, they might kill [the villagers] because they aren’t Sunni Muslims,” he said after hanging up one call.

The plumes of smoke visible near Bashir have now disappeared from the horizon, and those killed in the attacks have been buried. But for those who made it out of Bashir alive and are seeking refuge here, their only option is to wait. Within the four walls of the Shiite mosque, behind a heavily guarded wall of road blocks and metal fencing, Khalil and hundreds of other men, women and children sit cross-legged on the floor with nothing to do but exchange news and drink endless cups of tea.

“Our only demand is to go back to our village,” Khalil said as an elderly man next to him, his face wrinkled and weary, looked down in sullen silence. “We don’t want to leave our land.”

Abdulla Hawez contributed reporting from Kirkuk.