“I vote because I see images of immigrants from our neighboring countries drowning in the sea … We can easily be like them.” These were the words famous Iranian actor Hamid Farokhnezhad told a reporter in Tehran last Friday as he waited in line to vote. “It is not fair because many [candidates] have been disqualified,” he added. “But in this small space that is left for breathing, people try to get the maximum oxygen.”

Unlike the 2012 parliamentary elections that were boycotted by most reformists, these elections saw a high turnout in favor of the reformists. And Farokhnezhad was not the only star involved. Dozens of celebrities took to social media to encourage Iranians to participate in the elections and urged them to vote for the moderates. They published photos and videos to their millions of followers on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter — using VPNs for the sites that were blocked — asking them to vote for the coalition of reformists/moderates in order to eliminate ultra-conservative candidates. Famous actress Baran Kosari published a Dubsmash video with the voice of former President Mohammad Khatami. Dubsmash is a very popular app in Iran used by young Iranians to create short selfie videos of themselves with famous lines from a movie or song. Kosari used a line from Khatami’s video in which he asks the voters to vote for the “List of Hope,” an ideal candidate list compiled by reformists and moderates for the elections. The list for Tehran included 30 for parliament and 16 for Assembly of Experts, the clerical body that appoints the supreme leader, so Kosari wrote the numbers “30+16” on her palm and displayed it as the former president’s voice repeated, “vote for all the individuals in both the lists.”

Historic Coalition

Iranian elections may not be entirely free, but that doesn’t mean they don’t get competitive. The registration is fair — open to everyone who meets the minimum age and education requirements — so thousands of Iranians from all walks of life register for every election. But after registration comes the “qualification” process where different state and local entities do background checks on the candidates and approve or disapprove them. These entities include the Guardian Council, which makes the final decision of who is and who is not qualified to run. Dominated by conservatives, the council disqualified thousands of candidates from the race, including many reformists and moderates. Despite the mass disqualification of their candidates, all remaining reformists and moderates came together and formed a historic coalition and announced one unified list of candidates for the entire country — the “List of Hope.” Leader of the reform movement former President Khatami urged Iranian voters to vote for the entire List of Hope in order to prevent conservatives from winning seats.

U.S. Secretary of State Kerry talks with Iranian Foreign Minister Zarif after the IAEA verified that Iran has met all conditions under the nuclear deal on Jan. 16, 2016. (Kevin Lamarque/Pool via AP)

Nuclear Deal: A Uniting Factor

Unlike the U.S. Congress where the nuclear deal with Iran has become a dividing factor, the nuclear deal played an important role in uniting the moderates and reformists in Iran. The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or as Iranians call it, BARJAM, was one of the key determining factors in who got elected and who didn’t. Most of those who opposed the deal did poorly.

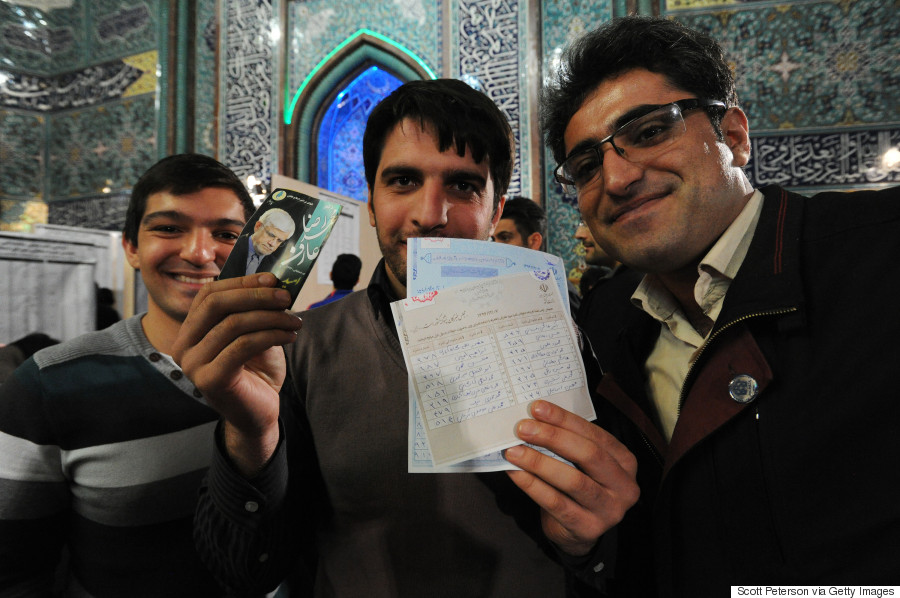

Iranian men hold up ballots marked with reformist candidates as they vote in key elections on February 26, 2016. (Scott Peterson/Getty Images)

Revolt In Tehran

Like most places across the world, parliamentary elections in Iran are more local than political. People tend to vote for candidates who can get things done and solve their local issues. The real political battlefield is in the capital, Tehran, where voters elect 30 members to the 290-seat parliament, or Majlis. The reformist voter turnout in Tehran was so unprecedented that the entire “List of Hope” candidates won 100 percent of the seats for Tehran, leaving no seats for ultra-conservatives. Even the most prominent conservative candidate Gholamali Haddad Adel, former speaker of parliament and a relative of the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei, lost to the List of Hope and came in 31. In a way, citizens used the ballot to disqualify the conservatives. The results came as a big shock to both the reformists and the conservatives.

An Iranian man shows Telegram app messages from supporters of a female conservative candidate on his mobile phone in Tehran, Iran on Feb. 24. (AP Photo/Vahid Salemi)

An App Called Telegram

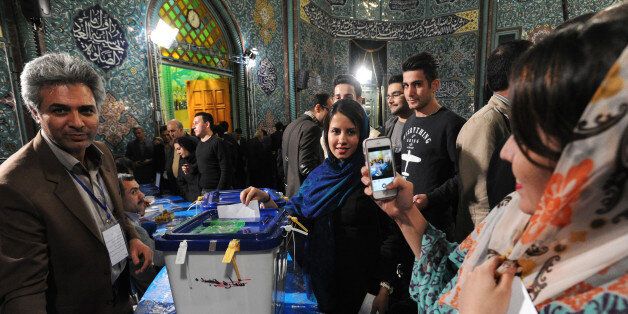

Since the 2009 election protests in Iran, Facebook and Twitter have been blocked by the government and Iranians have taken to using other social networks, including a new instant messaging app called Telegram with over 20 million users in Iran. Telegram became the most important campaigning tool in the most recent elections, especially for the reformists and moderates. Millions of people were sharing, forwarding and discussing participation in the vote, and hundreds of discussion groups and public channels were formed. The List of Hope was circulated by millions of users, and many saved it on their smartphones and took it to the polling stations on election day. Although the conservatives tried to block Telegram, the Rouhani administration stood up to pressures and refrained from blocking the Internet. That is why we saw many images of young voters on election day looking at their phone as they filled in the ballot with the List of Hope.

Winning With Tied Hands

Reformists and moderates entered a completely unfair race; many of their candidates were disqualified; both leaders of the Green Movement, Mousavi and Karroubi, were under house arrest; some top figures and activists of the reform movement are still imprisoned; and most importantly, there is a media ban on former President Khatami, leader of the reform movement. They had very limited access to national mass media such as radio and television, which are largely run by the conservatives, and had to use social media as their main campaign tool. Khatami had to publish his List of Hope video message on social media. It seemed as if moderates and reformists were competing with tied hands, and yet they were able to win.

Once again the Iranian people used the limited available democratic process, combined with unconventional tools and creative methods, to take another step towards political change. A slow process that started with the election of President Khatami and the birth of the reform movement in the 1990s continued through the 2009 election and post-election resistance, re-emerged in the 2013 election of moderate President Rouhani and again showed up in the two important elections last week. Iranians have been on a slow path to democracy and continue to progress — with patience and with hope.