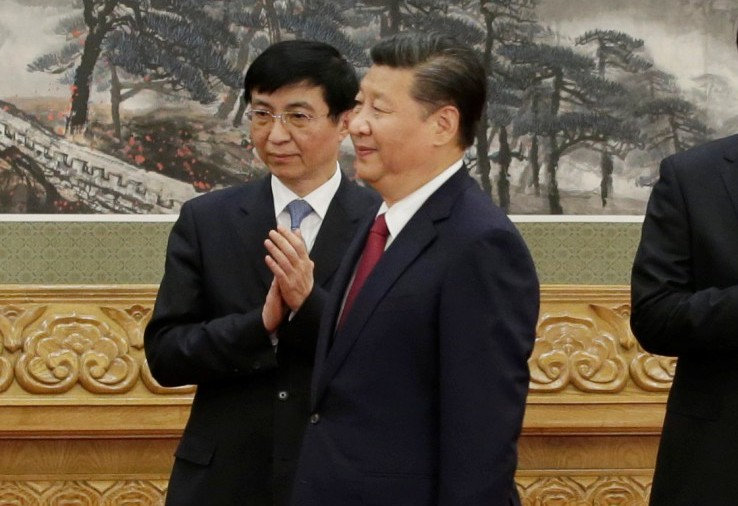

Yi Wang is a scholar of Chinese Studies at Griffith University and co-author of “The Hidden Ruler: Wang Huning and the Making of Contemporary China.”BRISBANE, Australia — The conclusion of the recent Communist Party congress in China has turned the world’s spotlight on a hitherto elusive figure, the 62-year-old scholar-turned-official, Wang Huning. Wang, who has just been elevated to the seven-member Politburo Standing Committee that rules China, is widely believed to be the mastermind behind the ideological frameworks set out by all three recent Chinese leaders — Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao and now Xi Jinping with his “Chinese dream.”

Wang’s writing over the years is so strikingly parallel to the policies Xi has adopted that he is regarded by many as the brain behind the throne, the mandarin behind the emperor. What Wang has written offers huge clues to understanding where China is headed.

On America

As President Donald Trump embarks on his first official trip to China, we can learn a good deal about what Xi thinks by examining Wang’s thoughts on America. In August 1988, while still a young but high-achieving academic at Fudan University, Wang won a prestigious scholarship to spend six months in the United States as a visiting scholar, staying at Iowa University for the first three months before traveling elsewhere, covering over 30 cities and nearly 20 universities, including three weeks at the University of California, Berkeley. From his diaries and notes on that six-month sojourn, he produced a book in 1991 titled “America Against America” in which he surveys the contradictions he saw in American society.

Citing examples from his firsthand observations, Wang pits the actual America as he saw it against the imagined America many have idealized. He highlights the contrasts between the world’s richest tycoons and impoverished American communities as well as between the much-touted democratic system and the “undemocratic” control exercised by the special interests of capitalism. For example, he compares American democracy and elections to shareholders in a corporation. In theory, he observes, all shareholders have a say; in reality, minority shareholders control the company.

The book covers such diverse issues as automation and what he calls the “commodification” of all aspects of society: sexual liberation, the “lonely American,” work ethic, hero worship, the power of science and technology, the hidden hand of the market, taxation, monetary society, Donkey-Elephant rivalry, pork-barreling, interest groups and lobbyists, county and grassroots politics, driver’s licenses as identification, local libraries, drugs and gangs, black people and native Indians. He discusses the “American spirit” in individualism and innovation and even comments on a famous book at the time by Allan Bloom, “The Closing of the American Mind,” which argued that higher education had failed democracy by imparting relativist values to whole generations.

On sovereignty

As Trump and Xi sit down this week to discuss bilateral issues, the notion of sovereignty will be looming large in both leaders’ minds. Xi’s thinking on this concept could well have been influenced by Wang, whose first book, based on his master’s dissertation, is on this very topic. Entitled “Guojia Zhuquan,” or “National Sovereignty,” the book traces the genesis and development of the concept in Western thought, contrasting it with the Chinese idea of zhuquan, or sovereignty, which predated its Western counterpart. The term zhuquan literally means the rights or power of the monarch and was adopted by the master-translator Yan Fu (1854-1921) as the Chinese equivalent for sovereignty when he translated “The Spirit of the Laws” by Montesquieu. Wang then addresses the evolution of sovereignty through different epochs, explaining its dual character as consisting of the domestic supremacy of the state and its independence from foreign influence.

Adopting a Marxist approach, he elaborates on the class-based nature of sovereignty, stating that supreme power is wielded by the ruling class of a given society. Wang then expounds on the theoretical literature on the topic, citing authors like Socrates, Augustine, Machiavelli and Hegel. He concludes by canvassing the significance of sovereignty for such contemporary issues as national independence, the developing world and, closer to home, the “Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence,” adopted by Mao Zedong — mutual respect for territorial integrity and sovereignty, mutual non-aggression, non-interference in internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence. He cites Marx, Engels and Lenin on the importance of national equality and self-determination.

On governance

As Trump and Xi compare notes on how to govern their countries, Wang’s ideas on governance may also come into play. In his writings, Wang emphasizes the importance of respecting the prevailing political, social and cultural conditions in China. He argues against “grafting” Western-style democracy onto the Chinese system, stressing instead that political democratization should not overstep the country’s developmental level, or “ba miao zhu zhang,” a Chinese proverb that means to “help a seedling grow taller by pulling it out of its soil.” He maintains that political reform should not be pursued at the expense of stability and that strong, unified central leadership is crucial to further reforms, which should be led by inner-party democratization rather than initiated from the outside.

Such expositions were characterized by Chinese commentators in the 1980s and 90s as the “new authoritarianism,” although Wang himself rejected that label. His views coincided with what the party leadership needed at that time in order to maintain control amid the rapid disruptions of the “reform and opening up” agenda. No doubt Wang’s views were responsible for his elevation in those days into the councils of Zhongnanhai, China’s equivalent of the White House. Quite obviously, these views still resonate with Xi’s instinct for enhancing control by the party.

On corruption

The Xi-Trump meeting may also touch on the central feature distinguishing Xi’s rule from previous regimes — his signature anti-corruption campaign. This also constitutes the theme of two of Wang’s books. The first is a sole-authored book called “Anti-Corruption: China’s Experiment,” published in 1990. Completed only three months after the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989, which was triggered by mass demonstrations against official corruption, the book was a timely and systematic treatment of the topic, citing both Chinese and foreign sources. The book examines the definitions of corruption in Latin, English and Chinese, differentiating Western and Chinese interpretations. He writes that while the West emphasizes malpractice mainly in the public domain, Chinese conceptions encompass both public and private domains.

The book covers historical lessons of past Chinese anti-corruption campaigns, the economic and psychological causes of corrupt behavior, and various types and techniques of corruption in a range of situations. Wang also offers ways to fight corruption through systemic control, including transparency, anti-corruption reporting, social supervision and standardizing rules of behavior for officials. Following China’s Confucian tradition, he also calls for moral education to raise the moral standards of the whole society and especially of officials who he believes must “internalize” ethical behavior.

The second book is a co-edited volume of articles from 1990 translated by Wang and his colleagues, compiled in the spirit encapsulated in the Chinese saying, “The stones from hills yonder can polish jade at home.” It means that by others’ faults, the wise correct their own. The preface emphasizes the Marxist methodology of historical materialism as essential in referencing overseas research on corruption so as to absorb foreign expertise according to China’s own conditions.

Wang’s prolific output has covered many other topics, including his prescient analysis of ecological and environmental challenges, which are overwhelmingly important to the residents of polluted Chinese cities today and a key element of Xi’s policies. Interestingly, despite his tight schedule preoccupied with high and dry politics, he also finds time to enjoy kung fu classics by Louis Cha, speaking highly of the author’s ingenious plot structures and bold imagination. He recommends the books to science students, whose creativity he believes can be stoked by Cha’s lateral thinking.

There is no doubt that Xi Jinping is his own man, who has accumulated more power to pursue his goals than any leader since Mao Zedong. But, Wang’s writings that hew so closely to Xi’s policies offer the best insight we are likely to gain into how those within the hierarchy of China’s opaque leadership think.

This article, drawn from a study published in the Journal of Contemporary China, was produced by The WorldPost, a partnership of the Berggruen Institute and The Washington Post.