ERBIL, Iraq — A young Kurdish fighter who introduces himself only as Akram mans a checkpoint to get into this northern Iraqi city, the afternoon heat rising from the pavement. He and his friend crack jokes and smoke cigarettes to make the long shift in the 100-degree heat go faster. And every so often, a few cars drive up, some with washing machines and satellite dishes strapped to their roofs, others with chickens fluttering in their trunks.

The day is relatively normal for the soldiers, despite the fact that the military checkpoint in Mosul just 500 meters away has been taken over by the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, an ultra-extremist group the international community is calling the world’s most ferocious terrorists.

ISIS launched a surprise attack earlier this week to take over several Iraqi cities, including Mosul — capturing its banks, prisons, official buildings and military checkpoints and bases. Not only is the group reportedly $425 million richer after looting Mosul’s central bank, it has also claimed most of the U.S. equipment, weaponry and vehicles the Iraqi army left behind when it fled the city. Its fighters are moving south toward Baghdad with eyes on establishing an Islamic caliphate stretching across Iraq, Syria and Lebanon.

But right now, there is no violent action on the road leading from Mosul to this city in Iraq’s semi-autonomous Kurdish region, unlike other areas in Iraq. And while many of those who fled Mosul say the group is out to terrorize and conquer, others say ISIS is treating civilians well and that they have crossed the ISIS-controlled checkpoint with ease. They say they prefer the group to Shiite Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki and his government, which they see as violent and alienating to the country’s Sunni minority.

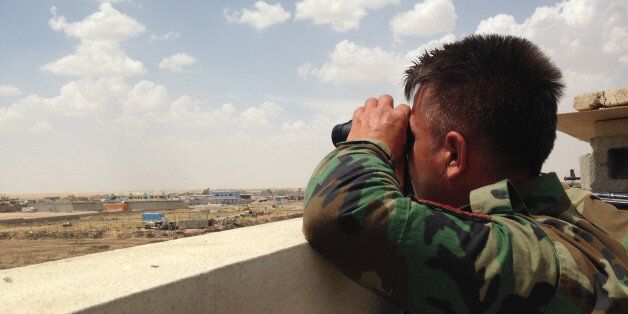

The Kurdish flag flies at a checkpoint in northern Iraq just 500 meters from an ISIS checkpoint in Mosul.

The Kurdish flag flies at a checkpoint in northern Iraq just 500 meters from an ISIS checkpoint in Mosul.

“The insurgents have taken Mosul, but their actions are calm,” said Arshad, an English teacher who only gave his first name for safety precautions. He said he’s leaving Mosul not because he’s afraid of ISIS, but rather because he fears the Iraqi government will bomb the city to eradicate the group. “There’s no violence [by ISIS] — it shocked us.”

Yousef El Eskandar, a middle-aged man who said he was heading into Erbil to buy a car — not to flee — said that ISIS is “liberating Muslims.”

“They are people of Mosul — not ISIS. They want to liberate Iraq from the tyranny of Maliki,” he said.

Yet for many of the thousands of Mosul residents who fled to Erbil, ISIS is known only for its brutal track record and violent reputation. On Friday, the United Nations warned of war crimes committed by the group, saying that it executed at least 30 Mosul residents believed to be working with the Iraqi police and security forces. The U.N. also said there are reports of women committing suicide after being raped by ISIS militants or forced into marriage. ISIS has claimed on Twitter that it killed 1,700 Shia soldiers in the city of Tikrit, though the report is unconfirmed.

Much of the international community, including the United States, is panicking over the possibility of Iraq spiraling into another bloody sectarian conflict. The ISIS takeover has caused many former Mosul residents to declare that they’ll never return if the extremist militants maintain control over their city.

A woman named Leyla, who declined to give her last name out of safety fears, fled with her young son several days ago and now lives in a small makeshift camp near Erbil for internally displaced Iraqis. She has no kind words for the group she says killed her brother, a local journalist in Mosul, nine months ago.

“I hate them,” she said as friendly volunteers passed out food to hungry families. “They aren’t Muslims. They kill people based on identification,” she added, referring to the militant group’s harsh interpretation of Sunni Islam and low tolerance for other beliefs.

A man living in the camp who goes by Mohamed said that ISIS is made up of terrorists. “All they want is to get power by violence,” he said while holding on tightly to his barefoot toddler’s hand.

While many of the former Mosul residents are gearing up for what could be a long, bloody battle, the Kurdish Peshmerga — the highly trained fighting forces of Iraqi Kurdistan — say they don’t expect a fight with ISIS over Erbil, even though Kurds are currently fighting the group in the oil-rich city of Kirkuk. There’s an “unspoken agreement” that neither side will start a fight near Erbil, they say, because the Kurds are focused on holding their territory, not fighting ISIS for Mosul.

Iraqi police and soldier uniforms lay strewn about outside a Kurdish checkpoint near Mosul after ISIS captured the city and the soldiers fled.

Iraqi police and soldier uniforms lay strewn about outside a Kurdish checkpoint near Mosul after ISIS captured the city and the soldiers fled.

The soldiers laugh at the idea of ISIS taking over Erbil. It’s “out of the question,” they said, mocking the Iraqi forces for fleeing Mosul in the dead of night, leaving their military uniforms, equipment, and even underpants in the dirt next to the Kurdish checkpoint.

Mahmoud Ahmed Hussein, a Kurdish brigadier general in charge of the city’s military checkpoint and base, doesn’t think they’ll have to confront ISIS, but he said his men are ready to fight to the death to defend their homeland, if need be.

“The international community calls [ISIS] terrorists. But right now, they changed their strategy,” he said to a room full of senior Peshmerga officers, alluding to what he described as a shift from violent tactics to a more tolerant rule in order to gain support. “It’s not in their benefit to kill people.”