ANTAKYA, Turkey — Azur Havre stands over a lunch of steaming meatballs in a courtyard owned by Sister Barbara Kallash, a quirky German nun who runs a guesthouse in this city roughly 10 miles from Syria’s border. He puts on a white yarmulke and says a quiet prayer in Hebrew before they eat. The two have been friends for decades, both members of dwindling religious minority communities.

Havre is a young 60, but he constantly worries about time. He says he’s one of the remaining 30 Jews in Antakya — often referred to by its biblical name, Antioch — and he’s the youngest.

“Antakyans are proud to have our community,” Havre says, sitting beneath a tree heavy with ripe oranges in Kallash’s courtyard. Just a short walk from the guesthouse is a mosque, a 100-year-old synagogue, and a Catholic church run by an Italian friar. “There is a brotherhood here,” he says, his sense of nationalism evident by the small metal Turkish flag pinned to his lapel. “We live together and share our lives.”

While the ancient city of roughly a quarter million people, mostly Muslims, also has a Christian population of just over a thousand, Jews and Christians here tell a story of diminishing communities as the Syrian civil war next door hits its three-year mark. Guesthouses and hotels in the city once catering to religious pilgrims are now frequented by aid workers, journalists and refugees. The sectarian clashes of the civil war, combined with economic hardship and lack of opportunity, are scattering religious minorities across Turkey and the rest of the world.

Jews first came to Antakya as traders in the year 300 B.C. when the city was a crucial stop on the Silk Road. Some religious traditions hold that the world’s first formal church was developed in Antioch, and the term Christian is said to have been used here for the very first time. As one Christian woman said when asked how long her family has lived in Antakya: “We’ve always been here, since the beginning.”

One of Antakya’s winding streets, where some of the homes are 200 years old.

One of Antakya’s winding streets, where some of the homes are 200 years old.

Throughout its long history, Antakya, which at its height was one of the most prosperous cities in the Roman Empire, has been been repeatedly conquered, attacked and reclaimed by a slew of rulers and religious groups. Everyone from the Persians to the Crusaders sought to control the city.

Despite its turbulent past, Antakya now thrives as a Middle Eastern city known for religious tolerance, with different cultures and faiths largely coexisting in peace. In little stores tucked away in the old city, merchants sell interfaith embroidery, pendants and paintings, most bearing a Jewish Star of David, a Christian cross, and a Muslim star and crescent.

And yet Christian and Jewish residents of the city say they have watched for years as younger generations leave for Turkey’s bigger cities in search of more sizable religious minority communities, jobs, and as one Christian merchant named Jacqueline put it: “a new world.”

Jacqueline, who asked that her last name not be used for fears of safety, worries there aren’t enough Christians for members of the younger generation to marry. And even if there were, it’s likely they would leave anyway. Gesturing to the quiet streets of Antakya, she laughs. “What would they do here?”

Havre’s 27-year-old daughter shared similar concerns, prompting her to move recently more than 600 miles away to Izmir, Turkey — where Havre says there are roughly 1,500 Jews.

The exodus of religious minorities has only been compounded by the bloody civil war in Syria, a country already facing divides between the Sunni Muslim majority and President Bashar Assad’s minority Alawite sect. About half of the Hatay province, of which Altakya is the provincial capital, is made up of Turkish Alawites, so the region has considerable support for Assad in some communities.

But with an influx of rebel fighters and tens of thousands of refugees — many of whom escaped starvation and deadly shelling by Assad’s forces — concerns are growing that sectarian clashes will cross the border to Antakya.

“The people who cause tension stay away,” Jacqueline says. “But I’ve heard whispers that this might be changing.”

Jacqueline and Havre both believe that Antakya will always have Jewish and Christian communities, yet both show obvious concern that the war in Syria could change things for the worse.

“We are strong. We don’t fear anything,” Havre says defensively. But then for just a moment, his tone softens. “The war in Syria is not a good thing for Antakya. There are al-Qaeda members here,” he adds, echoing a common fear in the city.

Havre describes a close connection between the religious communities in Antakya and Damscus, noting that he’s known 10 Jewish families across the border for as long as he can remember. Some Turkish Jews and Christians say they share bloodlines with Syrians, and that although a border divides them, their worries are one and the same.

Father Domenico Bertogli, the Italian friar who runs the church near Kallash’s guesthouse, and other religious leaders say the number of Christian groups visiting Antakya’s religious sites has dramatically dropped since the Syrian war began. In years past, hundreds of groups of pilgrims came through the city, each with roughly 25 people. Now, there is only a trickle of pilgrims, says Bertogli, who has lived here since 1988.

Father Domenico Bertogli walks from his Catholic church past the local mosque next door in Antakya’s old city.

Father Domenico Bertogli walks from his Catholic church past the local mosque next door in Antakya’s old city.

Bertogli has devoted much of his life to fostering an environment where Antakya’s religious history could be celebrated. When he first moved to the city, he says curious Muslims would approach the local church, asking about its story. The older woman who cared for it would tell them “they had the wrong address.” Now, he says, visitors of all faiths are not only common, but welcome.

“There are not many towns like Antioch,” he says, sipping on a glass of tangy limoncello made from the lemons hanging outside his window. “I have been here for 25 years and have never had problems. It is a truly tolerant town.”

Bertogli’s church is easy to miss, the sanctuary sheltered behind stone walls. But a bright yellow sign next to the mosque points the way, reading: Katolik Kilisesi, or Catholic Church. Everyone in the area, whatever their religion, knows his name. He’s akin to a city landmark.

For decades, Bertogli used to travel regularly to Syria, where he worked closely with Christian communities. But it’s been more than three years since his last trip, and he doesn’t know if he’ll ever return. The sectarian nature of the war concerns him the most, he says.

“Maybe one day [the Sunnis and Alawites] will have separate countries,” he says. “Reconciliation is very difficult. They have destroyed everything,” he adds, alluding to the Syrians and foreigners who are fighting Assad.

But just next door, Kallash shakes her head at any talk of war coming to the city.

Sister Barbara Kallash sits in the courtyard of her guesthouse in Antakya’s old city.

Sister Barbara Kallash sits in the courtyard of her guesthouse in Antakya’s old city.

“Antakya has been always a cradle of faith,” she says as the Muslim call to prayer resounds through the city. “Antakya won’t run into a clash of cultures like Syria. I think the spirit is very pure and open.”

On any given day, people of all religions and backgrounds gather at Kallash’s: Syrian refugees renting rooms, linguists studying Turkish, off-the-beaten-path travelers and pilgrims visiting religious sites, aid workers crossing into Syria, and Kallash’s local Jewish, Muslim and Christian friends coming for lunch.

Kallash has called Antakya her home for 38 years, after ending up in Turkey on a whim during a religious journey from her hometown in Germany to meet Mother Theresa in India. Before she reached her destination, a bishop offered her a posting in Antakya to house pilgrims coming through, and she agreed to try it out for a year or two. She recalls the hope she had for the small but strong community of religious minorities. Now, nearly four decades later, she still clings to that hope.

In a cave-like room off her courtyard, Kallash holds daily prayer sessions that anyone is welcome to attend. The wall is covered with different religious symbols and there are stacks of dozens of binders filled with sheet music to sacred songs from every religion imaginable.

On one recent afternoon, she grabs a guitar and waves Havre over to a wooden bench in the room. She turns to a page of his favorite Hebrew song and the two friends melt into harmony.

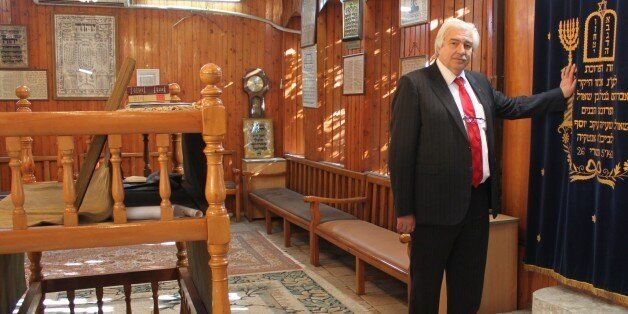

After Kallash takes a few quiet moments to pray for peace in Syria, Havre says he wants to go to the synagogue down the road. The temple is open mainly on religious holidays when an aging rabbi travels all the way from Istanbul to perform services. Havre is one of the only people who has a key.

A Turkish man stops outside of Antakya’s synagogue, just a short walk from a local church and mosque.

A Turkish man stops outside of Antakya’s synagogue, just a short walk from a local church and mosque.

Havre can name all of the Jewish families who used to live in the houses leading from Kallash’s guesthouse to the synagogue. While some of the houses are nearly two centuries old, with a few of the crumbling structures having survived deadly earthquakes in the 1800s, most of their Jewish inhabitants are long gone and Christian families now reside there.

It is the city’s history that Havre says makes Antakya a place like no other — a history he says needs to be reignited or it will disappear.

“I love this place,” he says, looking up at the sun-lit temple. He walks to an ark cloaked in blue velvet where 500-year-old Torahs are kept, and he gently places his hand on its door.

“The Jews will come back to Antakya as they did to Jerusalem,” he says. “God has promised it.”