Fighters with the Kurdish People’s Protection Units sit near a checkpoint on the outskirts of the destroyed Syrian town of Kobani on June 20, 2015.

Fighters with the Kurdish People’s Protection Units sit near a checkpoint on the outskirts of the destroyed Syrian town of Kobani on June 20, 2015.

AKCAKALE, Turkey — Standing at the Turkey-Syria border last week waiting for his relatives to cross from a warzone to protected NATO territory, Khalid Abu Suliman threw up his hands in frustration.

“What exactly is the Kurds’ stance?” the 30-year-old Syrian from Tal Abyad asked, eyeing a dozen slow-moving figures — his family — as they walked through the desert toward the border. “I can’t figure it out.”

Suliman’s relatives were among some 23,000 Syrians who fled into Turkey over the past two weeks, leaving their homes for fear of international airstrikes and clashes between Kurdish fighters and the extremist forces that call themselves the Islamic State, or ISIS.

The Syrian Kurdish militia — known as the People’s Protection Units, or YPG — has over that period taken territory in and around the Syrian border town of Tal Abyad from ISIS, with air support from the U.S.-led coalition. After their Tuesday capture of the town of Ain Issa, the Kurdish fighters now stand 30 miles from ISIS’s self-proclaimed capital of Raqqa — and the pressing question is what they will do next.

Smoke from a U.S.-led airstrike rises over the outskirts of Tal Abyad, Syria, on June 14, 2015.

Smoke from a U.S.-led airstrike rises over the outskirts of Tal Abyad, Syria, on June 14, 2015.

As has been the case throughout the four-year Syrian civil war, the obvious answer — go vanquish the extremists — looks far less attainable than international observers hoping for peace would like.

The Syrian Kurds, long alienated from the regime of Syria’s ruling Assad family and from the international community because of their ties to militant Kurds in Turkey, are today seen abroad as heroes because of the stand they took against ISIS in the Syrian town of Kobani last autumn. On Thursday, ISIS militants — accused by some of entering Kobani through Turkey — reportedly attacked the town with bombs, killing at least 30, many of them civilians.

Yet even as they have become favored partners for Washington in the U.S. attempt to rout ISIS, the Kurds are polarizing figures within Syria. The Assad regime long emphasized divisions between ethnic groups to prevent the growth of a united opposition. The result has been a fracturing between the nationalist Syrian Arabs, who lead the anti-Assad resistance, and the majority of the Syrian Kurds, who have carved out their own semi-autonomous regions in the northern part of the country while tacitly tolerating the Assad regime in some places.

The nationalist opposition accuses the YPG and its political ally, the PYD, of focusing on the narrower goal of independence for Kurdish Syria, and the animosity between the Arabs and the Kurds has become stronger as Turkey, wary of the Kurds, has boosted its support for the Arab anti-Assad forces. Any further advance into Arab-majority ISIS-held territory by Kurdish forces would therefore be complicated and potentially disastrous, analysts say, because the Kurds might not be able to gain the trust of traumatized locals any more than the extremists have.

“It’s all a political game,” said Faisal, one 24-year-old Syrian refugee in Turkey. “The Kurds want territory that stretches to the Iraqi border.” His relatives nodded in agreement from inside their makeshift shelter as volunteers handed out food and water.

Umm Ali, a middle-aged woman who last week was readying her family to cross back into Syria, told The WorldPost that she did not believe any of the players presently in Syria were worthy of her support.

“These are just international interests,” she said. “Everyone who is coming just wants to rule us. They don’t care about us.”

Syrian refugees receive water at the Turkish border in Akcakale on June 15, 2015, after fleeing intense fighting in northern Syria between Kurdish fighters and Islamic State militants.

Syrian refugees receive water at the Turkish border in Akcakale on June 15, 2015, after fleeing intense fighting in northern Syria between Kurdish fighters and Islamic State militants.

Last week, thousands of Syrians like Umm Ali returned to Tal Abyad and its new leadership, hoping to spend the holy month of Ramadan under their own roofs. But many others stayed behind, more willing to risk a life of destitution along with some 2 million other refugees in Turkey than the uncertainty of Kurdish rule back home.

“I’m not seeing anyone who knows how to rule now,” Umm Ali said as she contemplated life in a Kurdish-dominated society, even as a man crouched next to her chimed in with his unabashed support for the Islamic State because it brought a semblance of stability. “We’re between everyone’s feet,” she shouted over him. “Syria’s over.”

As far as Syria’s future is concerned, perhaps the most worrying of Syrian Kurd issues has been the organized opposition from other rebel groups fighting both ISIS and Assad — a sign that even as progress is being made on the battlefield, reconciliation will be very difficult among the various factions who may inherit Syria. Fifteen rebel groups earlier this month accused the Kurdish fighters of “ethnic cleansing” of Kurds and Turkmen in places like Tal Abyad.

The accusations are causing headaches halfway around the world in Washington. Though the U.S. and its partners against ISIS have long seen the Arab opposition groups as their key partners in Syria, they have grown steadily closer to the Syrian Kurds after the latter group became involved in Kobani’s defense in the fall. Obama administration officials — who consider some Arab-Kurdish unity a necessity — have this month scrambled to say that they are investigating the allegations of Kurdish human rights violations raised by Arab rebels, Turkish officials and some Syrian refugees.

“It continues to be important for anti-ISIL forces to make concerted efforts to protect local populations and property, and secure the human rights of all citizens,” White House press secretary Josh Earnest said on June 17, commenting on the Kurdish-led advances (and using the administration’s preferred term for ISIS). “This is essential to holding and stabilizing territory that’s been recaptured from ISIL. And that’s a message that we’ve obviously delivered in public, but it’s one that we continue to deliver to all of our partners as well.

Speaking on background to The WorldPost, a State Department official this week noted that the administration has consistently mentioned how Arab opposition forces have worked alongside the Kurds. The official also pointed to PYD and YPG promises to embrace displaced refugees who recently moved to Turkey and the Kurdish groups’ commitment to inclusive rule in the areas they have taken from ISIS.

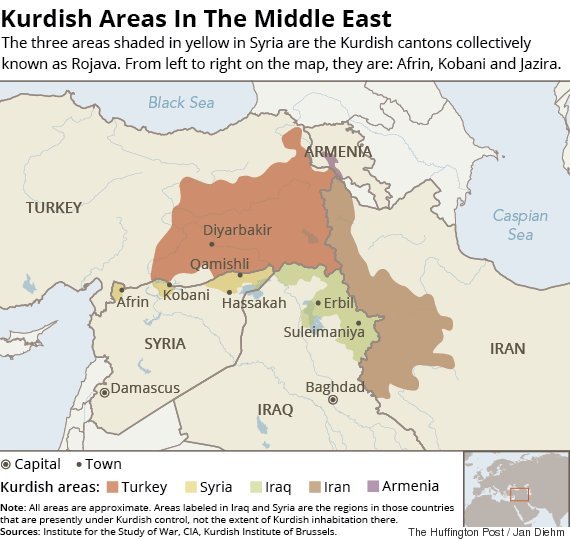

Over the past week, the Kurds have repeatedly tried to assuage fears among locals with such promises. They point also to the fact that Arabs live in the three regions of northern Syria — collectively known as Rojava — that are currently guarded by the YPG.

Mutlu Civiroglu, a D.C.-based Kurdish affairs analyst who regulars interviews officials of the militant YPG and political PYD while monitoring the region, noted in an interview with The WorldPost Wednesday that the largest Kurdish-controlled canton has two co-presidents: one an Arab man, the other a Kurdish woman.

Arabs, Assyrians and other Syrian communities “are not Kurds. Why would they be part of the system there if it was not representative?” he asked rhetorically.

In this photo taken from the Turkish side of the border, Kurdish fighters with the People’s Protection Units wave their yellow triangular flag on the outskirts of Tal Abyad, Syria, on June 15, 2015.

In this photo taken from the Turkish side of the border, Kurdish fighters with the People’s Protection Units wave their yellow triangular flag on the outskirts of Tal Abyad, Syria, on June 15, 2015.

Civiroglu added that he saw the complaints as “baseless” and fueled in part by Arab chauvinism and Turkish pressure on the Syrian Arabs to avoid working with the Kurds. He noted too that Arab brigades have fought alongside the Kurds for months. It was the fact that Arabs — from Raqqa — took part in Kobani’s defense with the Kurds that made that battle especially critical for the U.S.’s continuing involvement in Syria. The U.S.-led coalition has relied heavily on wooing Arab opposition to ISIS and Assad.

“The YPG is not only caring about Kurds,” Civiroglu said. “They consider everyone living in Rojava as part of Rojava.”

The leader of the chief political party tied to the YPG, Saleh Muslim, directly responded to Arab worries in an interview with Reuters on Wednesday by saying the Kurdish forces “don’t have a plan toward Raqqa so far.” According to Civiroglu, a greater priority for the YPG would be to push ISIS out of territory in Syria’s northeast or northwest, thereby widening the corridors — and in the west, creating a corridor — between Kurdish areas.

Muslim emphasized that on the question of trying to retake Arab-majority Raqqa, the Kurds would defer to other elements within the anti-ISIS opposition, particularly those in a position to challenge ISIS from within that stronghold.

“This [decision] is linked to the revolutionary forces in Raqqa. When they are ready to free Raqqa, to liberate it, perhaps the YPG will decide to support them,” Muslim said.

A Kurdish People’s Protection Units fighter holds her AK-47 in a camp on the outskirts of the destroyed Syrian town of Kobani on June 20, 2015.

A Kurdish People’s Protection Units fighter holds her AK-47 in a camp on the outskirts of the destroyed Syrian town of Kobani on June 20, 2015.

Syrians familiar with the situation in Raqqa sounded pessimistic this week when asked how they felt about a Kurdish role in an advance on Raqqa. Activists said ISIS has reportedly begun to prepare for that possibility by boosting security around its capital and arresting young Syrian men deemed too revolutionary or thought to harbor pro-Kurdish sentiments. Some with friends and family still in Raqqa said that while civilians are ready to rise up against ISIS, they may not do so if that meant the Kurds would then assume power.

“People are very excited that ISIS was defeated in Tal Abyad,” Abu Mohammed, one of the main activists behind the monitoring group Raqqa is Being Silently Slaughtered, told The WorldPost in Gaziantep. “People in Raqqa are anticipating their liberation. People want to get rid of ISIS — but they’re worried about who will rule them.”

“Blindly supporting the Kurds won’t bring a positive result,” he said, adding, “If someday Raqqa Is liberated through the Kurds, it will result in a civil war.”

According to Abdullah Mohammed, an activist with relatives still in Raqqa, suspicion of the Kurds is driving some young Sunni Arab men, who would have otherwise joined forces with the Arab nationalists battling ISIS and Assad, to stay put and wait things out.

“There’s a question mark stopping them from joining the FSA,” he said, referring to the loose Free Syrian Army coalition.

“We hope [the Kurds] don’t enter Raqqa,” he added, sitting in a hotel lobby in the Turkish border city of Sanliurfa. “It’s better if the locals join the FSA and liberate the city from ISIS. We don’t have anything to do with YPG.”

Sophia Jones and Hiba Dlewati reported from Akcakale, Gaziantep and Sanliurfa, Turkey. Akbar Shahid Ahmed reported from Washington. This piece has been updated to reflect that ISIS militants attacked Kobani on Thursday.