Nathan Gardels is the editor-in-chief of Noema Magazine. He is also the co-founder of and a senior adviser to the Berggruen Institute.

A political idea whose time has come is like technological invention: it can sit in the figurative garage or lab for a long while, like the internal combustion engine or personal computer, until sufficient social demand arises for its widespread adoption and dispersion. What is remarkable about the Trump-led Great Reaction is not that it happened, but that it took so long.

After all, the hollowing out of the white working class through the globalization of manufacturing has been going on for over two decades. And the commensurate rebellion against the political correctness that promoted gender and ethnic identities over a common culture in the universities and the media, and ultimately in electoral politics, troubled even the most liberal thinkers going back a quarter of a century.

It is hard to think of a more prominent liberal voice in America than that of Arthur Schlesinger Jr., the famous historian and aide to President John F. Kennedy. Yet, he was deeply disturbed by the identity politics he saw emerging as long ago as the early 1990s. In 1991 he wrote his reflections in a journal I edited at the time, New Perspectives Quarterly. He later published his full-throated thoughts in a 1992 book entitled “Disuniting America: Reflections on a Multicultural Society.”

From Civil Rights to Ethnic Upsurge

Schlesinger starts out his reflections in NPQ discussing the observations of Gunnar Myrdal in the 1950s when the Swedish social scientist traveled around the United States for his study on race. “Americans of all national origins, religions, creeds and colors,” he quotes Myrdal as writing, “hold in common the most explicitly expressed system of general ideals of any country in the West: the ideals of the essential dignity and equality of human beings, of inalienable rights to freedom, justice and opportunity.” Myrdal’s polling, Schlesinger notes, showed the determination of blacks even in that harshly discriminatory era to “hold on to this American Creed.” He goes on to argue that this belief was the driver of the civil rights movement. “The American Creed meant even more to blacks than to whites,” he writes, “since it was the great means of pleading their unfulfilled rights.”

By the 1970s, however, he observed a shift toward a different orientation as some intellectuals began calling for Afro-centrism and even separatism while some Latino leaders sought to carve out an identity pillar for their ethnic group. Schlesinger cites the Latino writer Richard Rodriguez as saying in those days that “the era that began with the dream of integration ended with scorn for assimilation.” Similar movements also arose around feminist and gender concerns.

The era that began with the dream of integration ended with scorn for assimilation.Richard Rodriguez

For Schlesinger, “this cult of ethnicity reversed the movement of American history, producing a nation of minorities less interested in joining with the majority in common endeavor than in declaring their alienation from an oppressive, white, patriarchal, racist, sexist, classist society.”

In short, as the celebrated historian put it, “The ethnic upsurge began as a gesture of protest against the Anglo-centric culture, but today it threatens to become a counter-revolution against the original theory of America as one people, a common culture, a single nation.”

It particularly worried Schlesinger that university campuses ― which should be the foremost platforms that bring people together in an open environment of exchange ― were fragmenting into a multitude of ethnic and gender silos with little tolerance for any notion of commonality. “A peculiarly ugly mood seems to have settled over the one arena where freedom of inquiry and expression should be most unconstrained and civility most respected – our colleges and universities.” And that was 1991!

He cited several examples from the office of student affairs at Smith College defining what he called a “litany of sins” from “ableism” to “lookism.” Here is the one on “Hetereosexism”: “Oppression of those sexual orientations other than heterosexual, such as gays, lesbians and bisexuals that can take place by not acknowledging their existence.”

Now, the Whitelash

Fast forward to how the identity mentality ultimately entered mainstream politics in the 2016 presidential campaign and caused what some are now calling a “whitelash,” though gender issues were also clearly an element. In a controversial article in last weekend’s New York Times, Mark Lilla observes that Hillary Clinton’s campaign championed all the diverse groups in America ― except for those in the white working class with religious convictions who, as we now know, turned insult into injury by voting for Donald Trump. As Lilla writes, Clinton slipped “into the rhetoric of diversity, calling out explicitly to African-American, Latino, L.G.B.T. and women voters at every stop. This was a strategic mistake. If you are going to mention groups in America, you had better mention all of them. If you don’t, those left out will notice and feel excluded.”

Hillary Clinton’s campaign championed all the diverse groups in America — except for those in the white working class with religious convictions who turned insult into injury by voting for Donald Trump.

Lilla goes on to admonish the partisans of identity politics and political correctness for “not recognizing how their own obsession with diversity has encouraged white, rural, religious Americans to think of themselves as a disadvantaged group whose identity is being threatened or ignored.” It was the haranguing rhetoric of that identity obsession, he says, which so grated not only the sensibility of Trump voters in the campaign, but others as well. “To paraphrase Bernie Sanders,” Lilla writes, “America is sick and tired of hearing about liberals’ damn bathrooms.”

Like Schlesinger, Lilla says the way forward is to rewind. “We need a post-identity liberalism, and it should draw from the past successes of pre-identity liberalism.” Such a liberalism, he writes “would speak to the nation as a nation of citizens who are in this together and must help one another.”

US Department of State

US Department of StateSchlesinger put it this way: “The republic embodies ideals that transcend ethnic, religious and political lines. It is an experiment that was reasonably successful for a while in creating a common identity for people of diverse races, religions, languages, cultures. But the experiment can continue to succeed only as long as Americans continue to believe in the goal.”

If Schlesinger were alive today, he would surely be horrified that a charlatan like Donald Trump could rise to power through divisive invective against Muslims, Mexicans and women, threatening to destroy the American republic from the reverse side of political correctness.

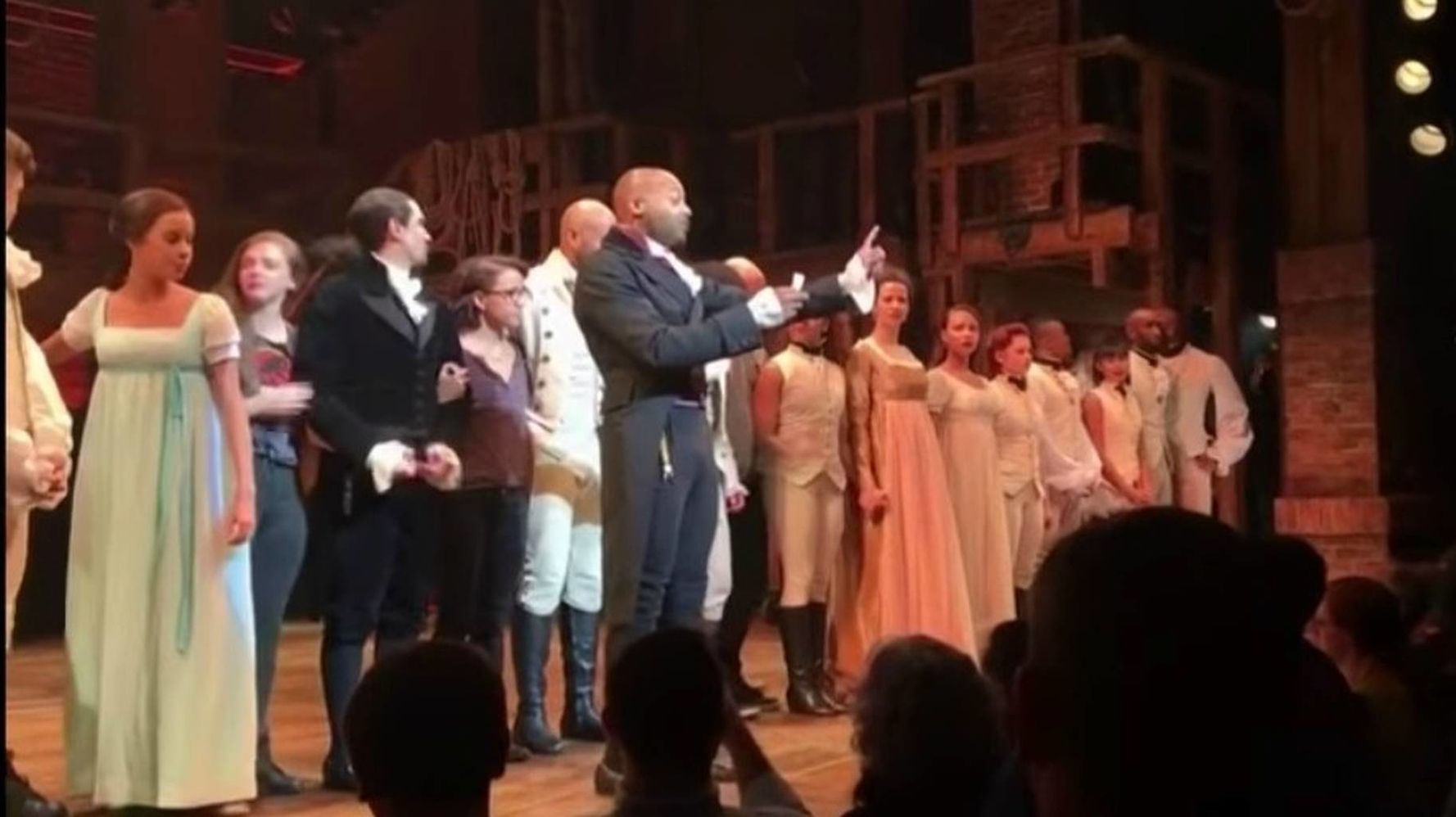

The danger now created by the Great Reaction, as Schlesinger would have seen, is the eruption of a protracted culture war between the “new America” and the “old America.” We have already seen the first skirmishes in the protest statement by the cast of “Hamilton” to Vice President-elect Mike Pence, who was in attendance. “We, sir, are the diverse America who are alarmed and anxious that your new administration will not protect us: our planet, our children, our parents, or defend us and uphold our inalienable rights, sir. But we truly hope this show has inspired you to uphold our American values and to work on behalf of all of us. All of us.” In response, Donald Trump angrily tweeted a demand that the cast “apologize.”

America, it appears, is on the cusp of realizing Schlesinger’s core worry: If a nation founded on the ideal of e pluribus unum ― “out of many, one” ― becomes pluribus without the unum, then it would be no nation at all.