Robert Hannigan was director of the Government Communications Headquarters, the United Kingdom’s intelligence and cyber agency, from 2014 to 2017. He is now European executive chairman of BlueVoyant, a cybersecurity firm, and a senior fellow at Harvard University’s Belfer Center.

LONDON — While its veracity remains in much doubt, Bloomberg Businessweek’s cover story — of Chinese spies allegedly hacking hardware manufactured in China and used by tech giants like Apple and Amazon — has once again raised the alarm about the risk to information technology’s global supply chain. To be clear, the tech companies involved, as well as government officials and experts, have denied or questioned elements of the story, arguing that much of the reporting is unsubstantiated. But whatever the truth of these particular allegations, such threats to our IT infrastructure are not new. The crucial challenge for the West is to prevent them from happening in the first place and to detect them when they do.

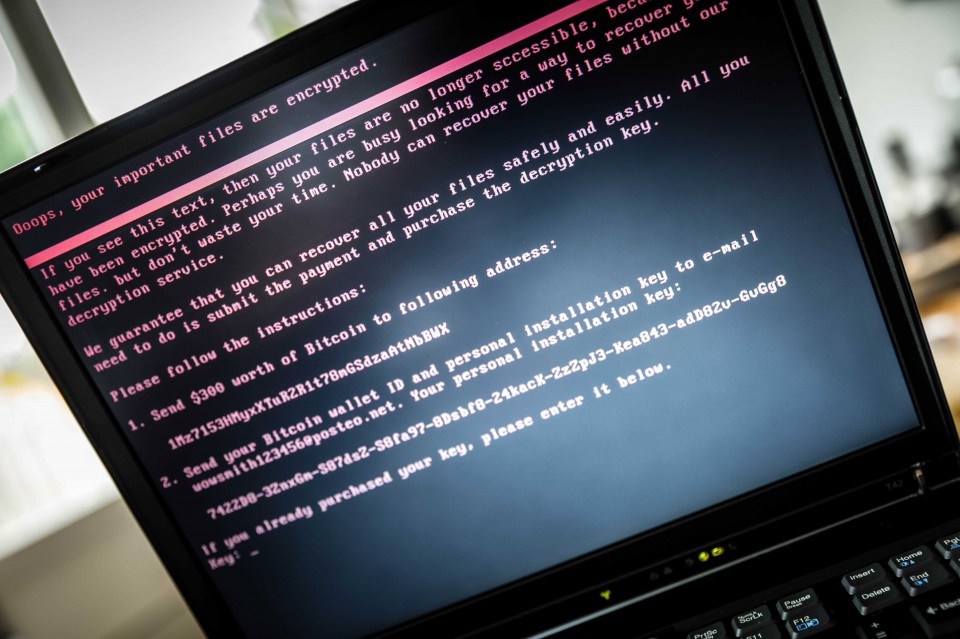

Over the years, as the arms race has accelerated between companies and hackers, both criminal and state, attacks have grown in sophistication. Companies who regard their own defenses as strong are now finding their once-trusted vendors, suppliers and customers becoming their greatest vulnerability. There are countless examples at the soft end of these supply chain threats: the email account of a lawyer hijacked to deliver malware to his utility company client or a genuine industry website infected to poison unsuspecting visitors from the energy sector. But these are at the lower end of the problem. The more strategic threat, as we have been made aware once again, lies in the fact that the developers of software and manufacturers of hardware are based in countries such as Russia and China.

In 2017, for example, the Russian military manipulated a regular upgrade in accounting software used widely in Ukraine, releasing a destructive piece of malware called NotPetya. This affected businesses across Europe that worked with the software, causing billions of dollars of damage. In the same way, the much-publicized allegations that Kaspersky Lab anti-virus software had been misused to enable Russian state access to some of its customers illustrates the potential for subversion on a huge scale. Such products offer the perfect opportunity to deliver attacks or gather information, if they can be co-opted or attacked, given that security products have to be given the kind of access to a network that attackers dream of.

Earlier this year, the American and British governments warned of Russian attacks against thousands of routers and network hardware worldwide. Such a malicious presence on the backbone of the Internet, whether through cyber attacks or, potentially, through building a hidden access into IT hardware during manufacturing, gives the attacker wide options to monitor, copy or change data, or to destroy it and disrupt the network.

The equation is not simple, however. Companies with roots and data in Russia are not automatically tools of the state. And just because much of the world’s IT is manufactured in China does not make all hardware produced there dangerous. But identifying potentially malicious “backdoors” is extremely difficult. Judging the difference between an engineering flaw or vulnerability and something more sinister often boils down to trust. And the fundamental problem is that in non-democratic countries, the tech sector is expected to behave as an extension of state power and the potential for its misuse is clear.

The answer cannot simply be to ban products made in a particular country. Even if American companies were to use local suppliers, the alternatives in the domestic market are not always there. While the United States may still have some options, for Europe and Asia, that ship has sailed. China will lead the world in many technologies by 2030, notably in some areas of artificial intelligence. Even for the United States, foreign-sourced technology will become unavoidable. Already, that which appears to be a U.S.-based supplier may have actually subcontracted the writing of its code many times over to the point where it has lost visibility.

What Western governments and companies must do is seek to understand their supply-chain dependencies and then find ways of identifying and meeting the risks, even when they are buried deep within the infrastructure of the Internet. This is a huge task and can only be accomplished by the combined efforts of the tech industry, which makes, owns and operates that infrastructure; governments, which have the job of protecting us; academia, to help develop technical solutions; and civil society, to hold the powerful to account.

Brad Smith, the president and chief legal officer of Microsoft, has been the driving force behind a Cyber Security Tech Accord, which aims to “improve the security, stability and resilience of cyberspace.” More than 60 companies have signed on and it is a welcome initiative, but the IT sector must go further by offering greater transparency about their own products and supply chains. Tech companies are notoriously secretive, and they have shown their much-hyped ethics, for example on customer privacy, to be elastic when confronted with the mesmerizing prize of the Chinese market.

Tech companies could do much more to build in security by default for new products and services, to prioritize the safety of customers and to collaborate on best practices. Together with governments, they could begin to restore security and reliability to an Internet that was not built with this in mind and which sometimes seems naive in the face of those who want to misuse it.

In the coming years, strong cyber defense will mean companies working hard to scrutinize their supply chains and impose their own restrictions on vendors. Governments will scramble to keep up. But the long-term goal must be to restore confidence in the global IT supply chain and to set and enforce standards that constrain those who abuse its trust.

This was produced by The WorldPost, a partnership of the Berggruen Institute and The Washington Post.