Nathan Gardels is the editor-in-chief of Noema Magazine. He is also the co-founder of and a senior adviser to the Berggruen Institute.

During the heady days of post-colonialism in the 1960s, the challenge which preoccupied the minds of the great development economists like Gunnar Myrdal was to figure out how the newly independent states of the developing world could escape from pervasive impoverishment and catch up with developed countries. His seminal book on the subject was titled “Asian Drama: An Inquiry into the Poverty of Nations.”

All kinds of strategies were promoted in those years, from India’s “License Raj” to Julius Nyerere’s egalitarian socialism of agricultural cooperatives in Tanzania to Kim Il-sung’s “self-reliance” in North Korea. Like Mao’s Great Leap Forward, with its infamous backyard furnaces to produce steel, these efforts all failed, some more spectacularly than others.

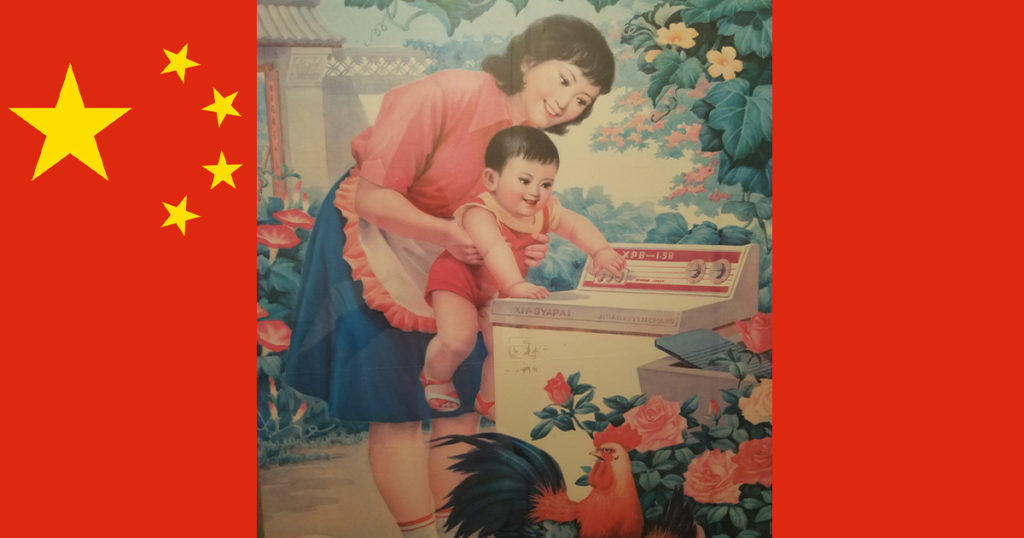

While such schemes came to naught, the so-called “Asian tigers” — Singapore, Taiwan, South Korea and Hong Kong — took off by following Japan’s example of engaging the global economy through a domestic mix of market competition, industrial policies and investment in infrastructure and education. In the wake of the disastrous Cultural Revolution in China, Deng Xiaoping learned from his neighbors and mimicked their course on a grand scale, embarking on a path that would raise 700 million people out of poverty into relative prosperity at a historically unprecedented pace over three decades.

Though he was accused by his Maoist enemies of taking the “capitalist road,” Deng called China’s new model “a socialist market economy.” As Hu Qili, the ideology chief on China’s Politburo back in 1988 put it to me on a visit to Beijing, “the market is not a feature unique to capitalism. Capitalism does not have the patent right over the market. What we are trying to create is a modality where the state regulates the market and the market guides the enterprises.”

The vast generation of wealth this approach unleashed among China’s billion plus population contributed mightily to the emergence of a global middle class, which has significantly narrowed inequality among nations. Myrdal’s inquiry about how to overcome poverty had its answer.

Initially, China was enthusiastically welcomed into the world economy as a nation that boldly came in from the cold of an ideological schism that had divided the planet. As year upon year of high growth rates improved China’ fortunes, it graduated by the early 2000s to a “competitor,” expected to behave as a “responsible stakeholder” in the U.S.-led global order. By 2018, it had grown in the eyes of official Washington into a “strategic rival” that many now regret “allowing” into the club.

This latter development rankles Chandran Nair. As he writes in The WorldPost this week from Gansu Province in China, “Given that China’s economic reforms and closer connections to the global market are what have helped to lift hundreds of millions of people out of poverty, and even provided a peace dividend, the argument that China’s ‘rise’ should have been constrained is an argument for keeping a vast population poor to protect a Western-dominated and self-serving status quo. Not surprisingly, many people outside the West — even those who are wary of Chinese growth and expansion — would be troubled by such a question and might even see it as racist.”

Behind the new animus toward China, as Nair alludes, is a dawning suspicion that the Western progenitors of globalization have been beaten at their own game and come out at a disadvantage. Indeed, the populist narrative that has taken hold across the West blames its ills on China’s success. Yet, as Singapore’s Kishore Mahbubani has pointed out in The WorldPost before, the perspective from Asia is quite different.

“Globalization has not failed,” he said in an interview. “All discussions on globalization are distorted because Western analysts focus on the roughly 15 percent of the world’s population who live in the West. They ignore the 85 percent who are the rest. The last 30 years of human history have been the best 30 years that the rest have enjoyed. Why? The answer is globalization. The rise of the middle class in Asia has spread wealth, faith in the possibility of fair international institutions and a stabilizing rules-based system that benefits the majority of humanity.”

“So why,” he went on, “is there a perception that globalization has failed? The simple answer is that Western elites who enjoyed the fruits of globalization did not share them with their Western masses.”

Former Mexican President Ernesto Zedillo, who now heads Yale’s Center for the Study of Globalization, concurs. In his view, Western leaders have deflected their responsibilities by failing to make the proper adjustments at home to a more equal distribution of wealth on a global scale. “Regressive tax policies, shrinking social safety nets, poor adjustment support, bad education and training policies and crumbling infrastructure,” he says bitingly, cannot be blamed on globalization or China. One could also add that the technological displacement of jobs and the declining labor share of national income as corporate profits soar cannot be laid at the doorstep of the Middle Kingdom.

Certainly, now that China has arrived in the top ranks of the global economy, it too needs to adjust to its new status by curbing mercantilist practices and agreeing to fair reciprocity in trade. In assessing the nature of the Chinese state, the West cannot and should not overlook the Uighur re-education camps, the ever-deepening system of surveillance and Beijing’s menacing moves toward Taiwan or freedom of expression and rule of law in Hong Kong.

But let’s assign culpability where it is due, and not where it isn’t. We are well beyond the age where making the West great again must mean that the rest of the world should remain in poverty.