Nathan Gardels is the editor-in-chief of Noema Magazine. He is also the co-founder of and a senior adviser to the Berggruen Institute.

In regional elections in Italy this week, the anti-establishment Five Star Movement, which rules the country in a coalition with the center-left Democratic Party, plummeted further in the polls from its high point in 2018, when it garnered almost 33 percent of the vote in the general election. Its short trajectory from rise toward demise is a lesson for all populist rebellions that transition to governing responsibility: When average citizens come to power unmediated by the deliberative filter of informed and reasoned debate conjoined with experience and competence, they will fall on their own sword. This has led some pundits to announce we are approaching peak populism.

Let’s be careful, however, not to throw out the baby with the bathwater. When representative government is locked up by the organized special interests of an insider establishment, the popular impulse to “participate, don’t delegate” — the Five Star slogan — remains a valid and realizable aspiration in an era when social networks have enabled more players to enter the political fray than ever before.

Whatever the electoral fate of the Five Star Movement, it has created some of the most innovative tools for citizen engagement in Western democracies, such as its online Rousseau platform that links its members in lieu of party organization and ideology, or Lex Iscritti, which enables citizens to propose and iterate legislation directly with their parliamentary delegates.

This is their real and lasting contribution. My sense from several conversations in Milan with Davide Casaleggio, one of the architects of these innovations, is that the import of the movement in his mind is that it has given birth to a new way of politics in which non-party networks linked by technology empower citizens not only to pressure elected governments or attain power, but to act outside established institutions to directly address their concerns.

This was also an idea of Adriano Olivetti, the visionary Italian industrialist and politician back in the 1950s, albeit with a key element that Five Star lacks. For Olivetti, an empowered citizenry must not only be informed in its deliberations, but complemented by a knowledgeable technocracy to administer government.

What all this suggests is that only when participatory politics is properly mediated and aligned with the expertise of competent administration can it become an antidote to populist explosions rooted in the indignation of citizens left out and left behind by governing elites. That is where deliberative democracy comes in.

Stanford University professor Jim Fishkin has been the prime apostle and practitioner of deliberative democracy for well over 20 years, with projects in over a hundred countries and jurisdictions ranging from Mongolia to California. Now history has caught up with this pioneer.

As a result of the crisis of representative democracy across the West today, Fishkin’s services are being called upon as never before to help mend the breach of distrust between the institutions of self-government and the public through the informed engagement of citizens in practices of governance once left to legislators alone.

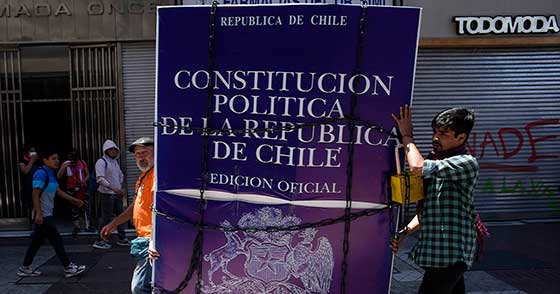

Indeed, drafting new constitutional rules through robust input from the public is at the top of the agenda in polities as disparate as Chile, where the issue is replacing a legacy charter from the waning days of dictatorship, to Iceland, where the digital-era challenge is to integrate crowdsourced amendments into the standing constitution. Both countries have invited Fishkin to employ his methods to mediate among contesting constituencies, which is at the heart of his approach.

Deliberative democracy involves using scientific sampling methods to recruit a body of average citizens indicative of the public at large to discuss and debate key issues in calm and sober settings — “islands of good will,” as Fishkin calls them. These islands are insulated from the electoral frenzy of partisans vying for power and the manipulative spin of the persuasion industry. All participants receive background information beforehand.

As in a jury trial, the aim is to introduce knowledge and objectivity into the process of citizen consultation and decision-making by hearing opposing arguments while bringing disinterested expertise to bear on the matter at hand — all presided over by trained mediators. Inevitably, in Fishkin’s long experience, citizens hew toward consensus and away from polarization once they are presented with the facts and context surrounding a decision.

In the wake of massive demonstrations met with police violence in Chile, the government, along with the main political parties and citizens’ groups, agreed that the current constitution, drafted in the period of transition from dictatorship when the shadow of General Augusto Pinochet still hung menacingly over the fragile reemergence of democratic elections and institutions, must be redrafted.

To that end, Fishkin’s Center for Deliberative Democracy, in conjunction with the Chilean senate and a major foundation, are hosting Deliberación País, which will gather around 400 people, chosen through scientific sampling in partnership with the University of Chile, over a weekend in the halls of the Chilean national congress to debate the terms of a new constitution.

The results will be taken by the members of a senate committee as a key input to draft bills on those terms, also taking into account some of the priority social concerns that emerged from a “national consultation,” in which 2.5 million people voted, in December last year.

In Iceland, the constitutional debate is quite different. It is not about expunging the past, as in Chile, but embracing the future of democracy in the digital age.

In early November last year, Fishkin’s center joined with the University of Iceland, the country’s prime minister and political parties to host what was called a “Deliberative Poll: Communal Consultation for the Revision of the Constitution.” In that exercise, more than 230 citizens, who were chosen to reflect the public at large, debated constitutional amendments, including those proposed through a parallel crowdsourcing exercise that was open to anyone with access to the internet.

Topics covered included the role of the president of Iceland, the court of impeachment and parliament’s power of indictment, whether constitutional amendments must be confirmed by referendum, whether referendums and citizens’ initiatives should be binding on the government, the drawing of electoral districts, weighted voting and the delegation of competencies in international cooperation.

The results were reported to the prime minister who has pledged to be guided by the poll in completing constitutional reform before the end of her term.

The type of deliberative democracy seen in Chile and Iceland is spreading rapidly to other democratic states.

In France, President Emmanuel Macron, who was politically wounded by the “gilets jaune” outburst over a rise in fuel prices aimed at reducing carbon emissions, has now convened a citizens’ panel on climate whose recommendations he may put up for a referendum vote later this year. As Macron said: “People want more democracy. They don’t just want to follow the laws, but to participate.”

This year, New Zealanders will hold a series of referendums on euthanasia and the legalization of cannabis and abortion, which they call “conscience votes,” to guide the parliamentary agenda on these controversial issues.

For citizens, deliberative democracy offers a robust platform for their voices to be heard and heeded. For the good governance of society, it avoids the populist sins of ignorance, demagoguery and utopian fantasies by introducing expertise and practices of reasoned deliberation into the great opening toward citizen engagement enabled by digital connectivity. Populist politics will peak when deliberative democracy advances as a more responsive and effective alternative.