Nathan Gardels is the editor-in-chief of Noema Magazine. He is also the co-founder of and a senior adviser to the Berggruen Institute.

For writers like Pankaj Mishra, the long tail of this reaction now afflicting the West itself spells “the endgame for the whole of civilization” of the exhausted march to modernity that began back in the 18th century. That future is now behind us.

The great literary journalist Ryszard Kapuściński, who reported on the revolution, identified back then the thread that would tie all these successive movements together. For Kapuściński, change was so rapid that the average person was unable to absorb it. The technocratic character of modern values ignored the communitarian and religious dimension of people’s lives, threatening the “most elemental part of their identity.” As a result, “even more emphasis was placed on older values. People defended themselves by hiding in these older values. The old traditions and old religion were the only shelter available to them.”

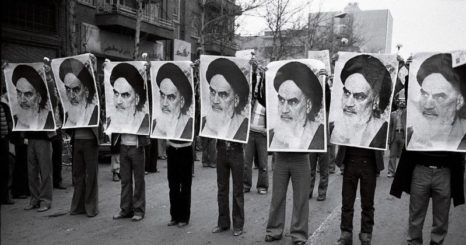

For Kapuściński, “the Iranian revolution opened a new period in Third World countries — the period of cultural decolonization. But this counter-revolution cannot succeed. It is not creative but defensive. It remains defined by what it resists. It leads to paralysis.”

Here too, the defensive character that continues to define the Iranian revolution so many decades later presages the fate of today’s populist revolts as well. Absent a constructive vision, politics that dwells in the past only leads to the impasse of a stalled future.

In an interview with The WorldPost, the first president of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Abolhassan Bani-Sadr, reflects on how the revolutionary project in which he played a central role went wrong.

“Iran was being held down by its consumer-oriented economy based on exporting crude oil and importing goods from the West — a closed-circuit relationship dominated by the shah’s regime inside and Western interests outside,” Bani-Sadr recalls his thinking back in the late 1970s. “The only way the country could develop would be through an open social system, in which relations are not regulated by force and domination but by rights guaranteed and exercised by the people themselves. It was on this basis that we were able to build a consensus to challenge the shah and his puppet relations with the West.”

When Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini was forced into exile in 1978 by the shah, he came to Paris and joined in a kind of united front with Bani-Sadr’s group. “Our hope then was that if the clergy committed itself to these principles, there would be no obstacles to their implementation once the shah was forced out,” the former president recounts. “Though Khomeini had promised to implement this approach when he was exiled in Paris, after his return to Iran in 1979, he instead sought to establish authority by reconstructing despotism through theocratic rule. We now know that he had plotted that in secret while still in Paris. If I had known then what I know now, I would have done my utmost to expose this plan in order to make it hard or impossible to implement.”

Even wily conspirators like Bani-Sadr underestimated the ruthlessness of the ayatollahs and their centuries-old organizational infrastructure tied to the pull of the past.

From his home in exile just outside Paris, Bani-Sadr takes the long view. “Revolution is the beginning of a transformation, not the end of it,” he says. He notes that the various upheavals in Iran over the course of the 20th century have removed all but one of the main pillars of despotism. The monarchy has been overthrown and the market power of the large landowners and bazaar economy has been dismantled. The nation is now fully sovereign without its historical dependence on any outside powers. Only the political rule of the clergy remains, and that is waning.

“Today, at long last, the clergy’s legitimacy is in drastic decline,” the old revolutionary argues. “The majority of the clergy oppose and have distanced themselves from the ideology of the ruling regime. To maintain its fragile hold on power, the ruling clergy seeks to foment and sustain crises with foreign powers. The creation of such crises has become intrinsic to the nature of the Iranian regime since the days of Khomeini.”

The great irony for Bani-Sadr is that America’s intensifying hostility toward Iran in the Trump years only plays into the hands of the theocrats, reinforcing the defensive character of the regime and blocking any path forward toward a constructive politics from the bottom up that was the original aim of the revolution.

“Despotic structures from within combined with the assistance of foreign powers from without has created big obstacles to a homegrown republic, frustrating the aspirations of most Iranians,” he says. “They are the evil twins that reinforce each other. In Iran, the people will do their part and one day will bring the revolution to its logical conclusion — a ‘republic of citizens.’ If the West really wanted to help realize the original promise of 1979, the wisest thing to do would be to find ways to decrease confrontation with the regime instead of finding ways to increase it. In the present moment, Trump is the co-conspirator with Khomeini’s heirs in keeping the Iranian people down.”

Across the world, bottom-up revolts against top-down modernizers and global elites will exhaust themselves sooner in some places, later in others. Then a constructive politics of renovation can emerge that is defined by the future it embraces instead of only by what it resists. Bani-Sadr’s hope against hope is that Iran can once again lead the way if only the old ayatollahs and the new populists stop reinforcing each other.

Writing from New Delhi this week for The WorldPost, famed chest surgeon Arvind Kumar says India’s pollution crisis is “a public health emergency” and calls for the rapid phase-out of fossil fuels. As the U.S.-China trade talks head into their final weeks, the U.S. trade representative under President Obama, Michael Froman, says the outlines of a deal are already there — the bilateral investment agreement nearly completed before the Trump transition. And finally, writing from exile in Miami, former Venezuelan general Antonio Rivero explains why the military has not turned against President Nicolás Maduro — yet.