Nathan Gardels is the editor-in-chief of Noema Magazine.

It is startling how rapidly things can fall apart. After so many decades of normalized stability in the United States, no doubt with both plenty of racial injustice as well as deaths of despair among the white working-class underneath, it suddenly all rises to the surface and explodes. Nothing ever changes, until it does.

The most sobering conversation I’ve had of late was with a former governor of California who knows American politics as well as anyone, if not better. He laid out a frighteningly plausible scenario: The chaos and violence in the streets of American cities these days — the latest incendiary incident being the bald assassination attempt on two young patrol officers in their squad car in Los Angeles last week — will drive that margin of voters whose ballots count most into the arms of Trump’s law-and-order reelection narrative. If they need further cause to cast their votes his way, it is the radical demands to defund the police and the blinkered cancel culture that visits so many sins of the past upon a hapless mainstream that is only trying to get by.

If Trump is returned to office, the scenario runs, the streets will erupt tenfold since there is nothing left to lose. In turn, an even harsher crackdown will follow by an already impeached and reelected president unleashed from any constraints. America, brace yourself.

The breathless pace of the unraveling we are witnessing in the U.S. brings to mind Jared Diamond’s observations in Noema of the parallels with what happened between 1967 and 1973 in Chile, when Latin America’s most enduring democracy broke down virtually overnight and gave way to a dictatorship that lasted 17 years.

Diamond, whose most recent book is titled “Upheaval: Turning Points for Nations in Crisis,” doesn’t foresee any kind of sharp military coup as happened in Chile, of course. Rather, he sees a rupture that results from the dissolution over time of trust in impartial institutions and thus scant capacity for compromise to reach a governing consensus. Demonization of “the other” first creeps into the rhetoric of partisans, paralyzes governance and then spills into open confrontation on the streets. “It is a process of erosion that at some moment reaches a point of no return,” he says. “I don’t take it for granted that democracy in the U.S. is going to overcome all obstacles. I see a serious risk.”

The underlying conditions behind the slow erosion leading up to this moment in the U.S. have been a long time coming, as Jack A. Goldstone and Peter Turchin wrote in Noema last week. In fact, they predicted the “turbulent twenties” we are now experiencing decades ago. Goldstone warned that “in the 21st century, America was likely to get a populist, America-first leader who would sow a whirlwind of conflict.” Turchin foresaw that “the U.S. was heading toward the highest level of vulnerability to political crisis seen in this country in over a hundred years.”

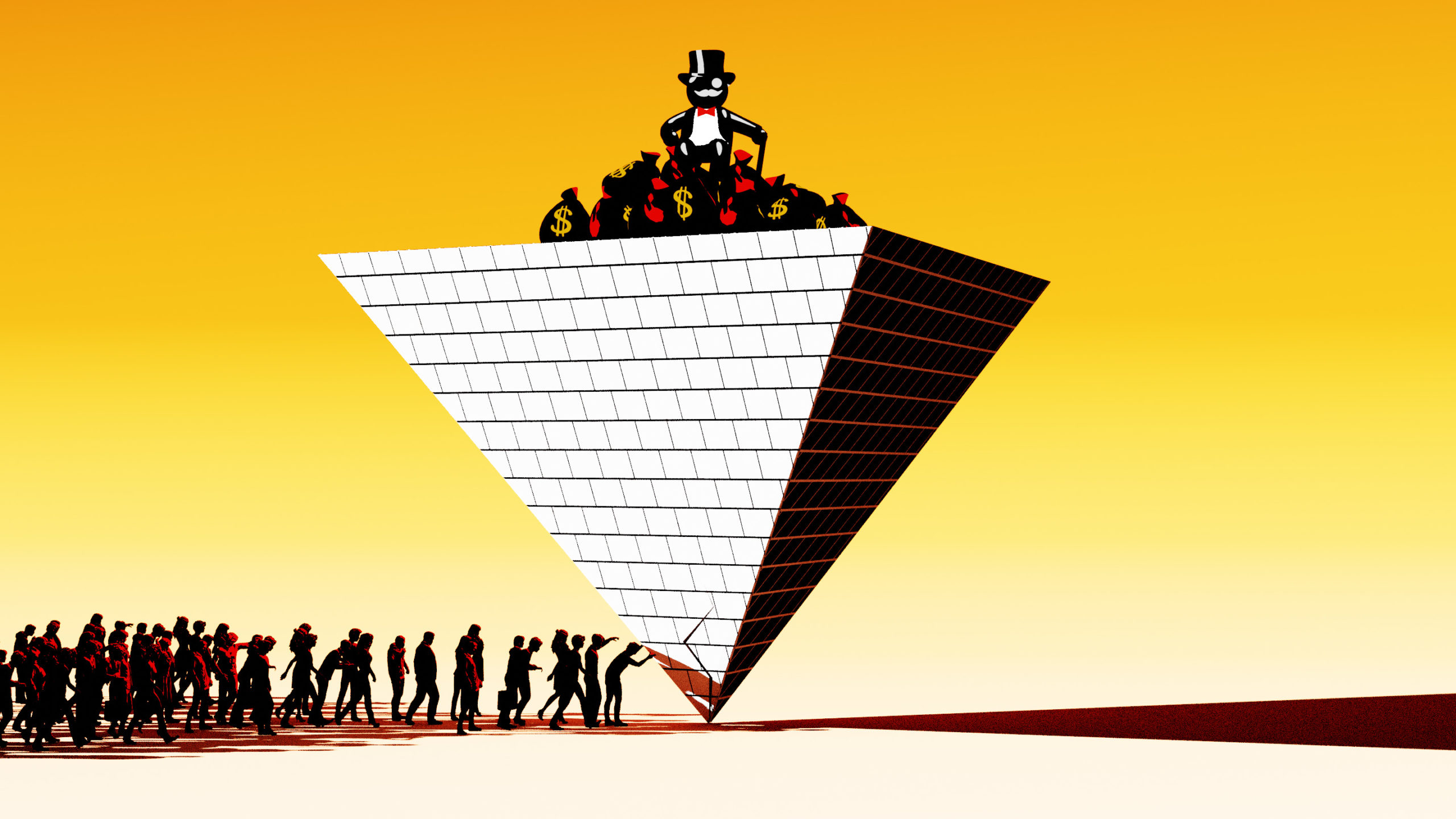

The core of their predictive model is based “on the fact that across history, what creates the risk of political instability is the behavior of elites” who commit what the authors call “three cardinal sins.”

As they state it:

First, faced with a surge of labor that dampens growth in wages and productivity, elites seek to take a larger portion of economic gains for themselves, driving up inequality. Second, facing greater competition for elite wealth and status, they tighten up the path to mobility to favor themselves and their progeny. …

Third, anxious to hold on to their rising fortunes, they do all they can to resist taxation of their wealth and profits, even if that means starving the government of needed revenues, leading to decaying infrastructure, declining public services and fast-rising government debts.

Such selfish elites lead the way to revolutions. They create simmering conditions of greater inequality and declining effectiveness of, and respect for, government. But their actions alone are not sufficient. Urbanization and greater education are needed to create concentrations of aware and organized groups in the populace who can mobilize and act for change.

Top leadership matters. Leaders who aim to be inclusive and solve national problems can manage conflicts and defer a crisis. However, leaders who seek to benefit from and fan political divisions bring the final crisis closer. … Each side works to paint the other as a fatal threat to society, creating such deep polarization that little of value can be accomplished, and problems grow worse until a crisis comes along that explodes the fragile social order.”

If it all sounds so familiar, it is not only because we have been living through the consolidation of a plutocracy, but because we’ve seen this dynamic again and again in history. Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson made a similar point in their 2012 book, “Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty.”

Their essential argument is that when an “extractive” economy controlled by political elites for their own benefit displaces an “inclusive” system that raises all boats, the end is near.

As a warning to the U.S., they offered the lessons of Venice in the Middle Ages. A system of seafaring trade open to new players led to the incredible wealth of the city-state, in those days the richest place on earth. When the top families circled the wagons to protect their own spoils and blocked the upward mobility of others, it all fell apart.

“In Venice,” Acemoglu told the Christian Science Monitor, “things started unraveling not when economic inequality increased but when political inequality increased — when a particular group of merchant families worked to seal the system to start monopolizing political power.” That, as Acemoglu has pithily put it, “is how Venice became a museum.”

Only time, and a short time, will tell if America heads further down this path that it is already on. It may be, as the former California governor is fond of saying, that “there is always breakdown before breakthrough.”

When that chance for breakthrough arrives, there are no quick turnarounds. The nature of structural crises is that, since they are a long time in the making, they will be a long time in the mending.