BEIJING — Chinese authorities rang in Sunday’s International Women’s Day with a contradiction: celebrating the country’s first draft law on domestic violence while simultaneously arresting feminist activists who have campaigned for these legal protections.

Fellow activists and lawyers representing the women say that an initial police sweep across multiple cities on March 6 netted 10 activists, five of whom were released after short detentions. But as of Monday evening, five women remain in custody, one of their lawyers said: Li Tingting, Wei Tingting, Zheng Churan, Wu Rongrong and Wang Man.

The five activists who are still detained in China.

The five activists who are still detained in China.

Some activists from women’s rights groups, many of whom also work on LGBT issues, have gone into hiding after hearing that police came to their homes or offices. Beijing police declined to answer questions over the phone and did not respond to faxed questions about the detentions.

According to activists who worked closely with the detained women, the arrests were made just a day before several small-scale actions were planned. Women in different Chinese cities planned to highlight sexual harassment on public transportation by putting stickers on buses saying “Catch sexual harassers: come get’em, police!”

But the police appear to have come for the activists instead.

Although the protests were timed to coincide with International Women’s Day on March 8, the women may have been detained for another reason: China is currently in the midst of the annual National People’s Congress, a multi-week political bonanza during which Chinese activists must tread particularly carefully or risk detention.

A military conductor leads a band during the opening session of the National People’s Congress at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing.

A military conductor leads a band during the opening session of the National People’s Congress at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing.

“We took into account how sensitive things are during these sessions, and we couldn’t have been any more ‘gentle’ with our choice of actions,” said one fellow activist, who spoke on condition of anonymity due to fear of arrest. “That’s why we were so surprised, so shocked.”

Several of those who were arrested are leaders in a wave young feminist and LGBT activists, who have garnered national attention with creative forms of protest. Li Tingting, who often goes by the pseudonym Li Maizi, first became known for organizing the “Occupy the Men’s Bathroom” movement in 2012, a protest that drew attention to gender equality issues, in particular the need for more women’s public toilets to alleviate long waits.

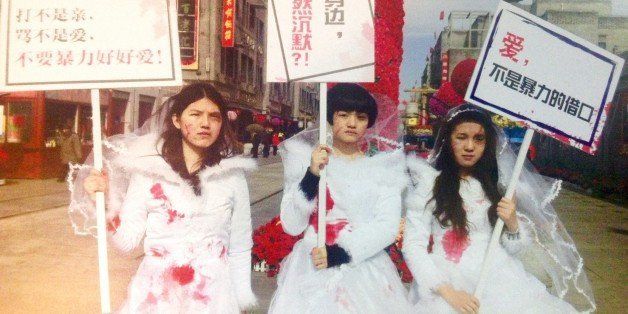

Li and activist Wei Tingting also took part in “Bloody Brides” protests, walking around central Beijing dressed in wedding gowns splattered with fake blood to raise awareness about domestic violence.

Those efforts combined with two high-profile domestic abuse cases to raise support for China’s first-ever national law on domestic violence, which is currently before China’s National People’s Congress.

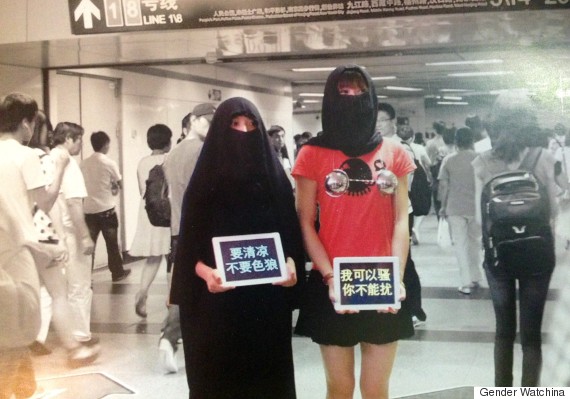

Two women in Shanghai protest comments blaming the revealing clothes women wear for sexual harassment on the subway.

Two women in Shanghai protest comments blaming the revealing clothes women wear for sexual harassment on the subway.

But that legislative endorsement of the activists’ work provided no shelter from capricious crackdowns on unauthorized public demonstrations. Since coming into power in 2012, President and Communist Party General Secretary Xi Jinping has overseen a sweeping anti-corruption campaign, as well as a crackdown on civil society groups ranging from human rights lawyers to NGOs building libraries in rural China. Feminist and LGBT activists say their events are frequently monitored or shut down by local police.

Lawyers for some of the detained activists said they have not been able to speak with their clients since their detentions on Friday and Saturday. According to accounts from fellow activists, the women were mostly arrested at their homes, with police sometimes arriving in the middle of the night and searching cell phones and computers.

Although the police have not communicated the charges to the women’s lawyers, fellow activists told The WorldPost that during one of the arrests, police cited the notoriously nebulous crime of “picking quarrels and provoking troubles,” a catchall crime often used to detain activists or dissidents.

Fellow activists say that the women’s real crime was to gain a substantial following, particularly in China’s buzzing microblog services. The women’s supporters made their voices heard following this year’s Chinese New Year’s Gala, an annual broadcast that attracts nearly 700 million viewers. After the program contained multiple skits mocking unmarried or unattractive women, Chinese feminists circulated online petitions demanding an apology from China’s state broadcaster, a call that was partially echoed even in Chinese state media.

“People here are finally listening to the voice of China’s feminists,” said one activist who spoke on condition of anonymity. “Just a few years ago we were really marginal and weak, but because of the hard work of the last few years the authorities now see our ability to influence and rally people.”

But much of that influence emanates out from a very small core group of activists, five of whom remain in detention.

“At this point we’re still quite weak,” the activist lamented. “If they want to snuff us out they could do it.”