According to Greek myth, after the creation of humans and animals, the gods assigned Prometheus and his younger brother Epimetheus to allocate their capabilities. The brothers were Titans, a race of divine beings. Epimetheus requested the privilege of assigning the various powers and characteristics to the creatures on Earth, promising that Prometheus could then inspect his work.

Epimetheus began sorting out the natures of the animals of land, sea and sky. So absorbed was Epimetheus in the task of ensuring their survival — with speed, strength, agility, keen eyesight and hearing, a superb sense of smell, venom, camouflage, wings, feathers, fur, scales, fangs, talons, hooves and horns — that he absentmindedly used up all the abilities on non-reasoning beings. Just as his brother Prometheus, whose name means “forethought,” arrived to inspect the creatures — and on the very day they were destined to emerge on Earth — Epimetheus, whose name means “afterthought,” realized with a start that there was nothing left for the naked, defenseless humans.

Plato relates that Prometheus was “desperate to find some means of survival for the human race,” so he appropriated the technology of fire from the gods to bestow on puny mortals. With the gift of fire, men and women could make tools and figure out ways to compensate for their pitiful physical shortcomings.

In this ancient “speculative fiction” about humanity’s relationship with technology, the gifts bestowed by Prometheus represent the first human enhancements — the first attempts to overcome the limitations of the human body by natural or artificial means. Prometheus’s gift to humanity keeps on giving, with potential for both positive and worrisome ramifications. It is techne — craft — along with intellect, imagination and audacity that are the unique gifts that human beings rely on to survive in the world. “Technology makes up for our absurd frailty,” the American philosopher of ethics and technology Patrick Lin has written. “We naked apes couldn’t survive at all, if it weren’t for our tool-making intellect and resourcefulness.”

“‘Technology makes up for our absurd frailty.’”

Artificial improvements to overcome the limitations of the human body and to expand natural strength, sensory apparatus and abilities — now known as human enhancement technologies — may seem like cutting-edge science. We often hear both pessimists and proponents claim that our current technology — including artificial intelligence and genetic engineering — is unprecedented, unique to modernity. Yet the concepts of augmenting human capabilities are ancient, as are the qualms they evoke. Time-traveling back to antiquity might help us think about the human transformations of the future.

The very earliest tools — stone hammers, spears, the atlatl, the bow and arrow — can be considered the first human enhancements because they extended a person’s reach and aim and exerted force. In classical Greek antiquity, bows and arrows, even when wielded by great mythic heroes like Hercules and Odysseus, were sometimes criticized as cowardly weapons, akin to ambush, because they allowed one to kill from afar or in an underhanded way without facing an adversary in hand-to-hand combat. Catapults, developed in the fourth century B.C.E., carried forward the trajectory of human enhancements for warfare, which continues unabated. When he was shown one of the first torsion catapults in action, the Spartan general Archidamus famously declared that the invention marked the end of human valor in battle.

Greek myths envisioned borrowing the enviable powers of gods and animals to compensate for human vulnerability. These myths represent some of the earliest science fiction, and where imagination leads, innovation follows. Besides archery and catapults, we have many historical examples of human enhancement technologies in antiquity, from prosthetics of surprising ingenuity to developments in military armor. The desire to enhance human capabilities is timeless, and it is striking to see how mythic and historical examples foreshadow modern advancements — and drawbacks — in trying to improve nature.

Human Enhancements In Myth

Plenty of myths and legends turn on the folly of seeking immortality. But if turning back old age and postponing natural death were impossible, then could mortals at least hope to enhance their physical capabilities? Humans were so feeble compared to the gods; even brute animals enjoyed more magnificent powers than the most robust men and women. In classical antiquity, a thought-provoking group of mythic tales about artificial life investigated whether “biotechne” — “life through craft” — could be used to upgrade nature and somehow engineer hyper-human abilities.

Today, human enhancements — including visual and hearing aids, titanium joints, artificial heart valves, bionic prosthetics and an array of medicines — are commonplace and welcomed. But controversies arise over some human improvements and supernatural enhancements slated for questionable uses. People start to worry when, for example, corporations create lip-reading and facial-recognition software and claim that only good uses will be made of them.

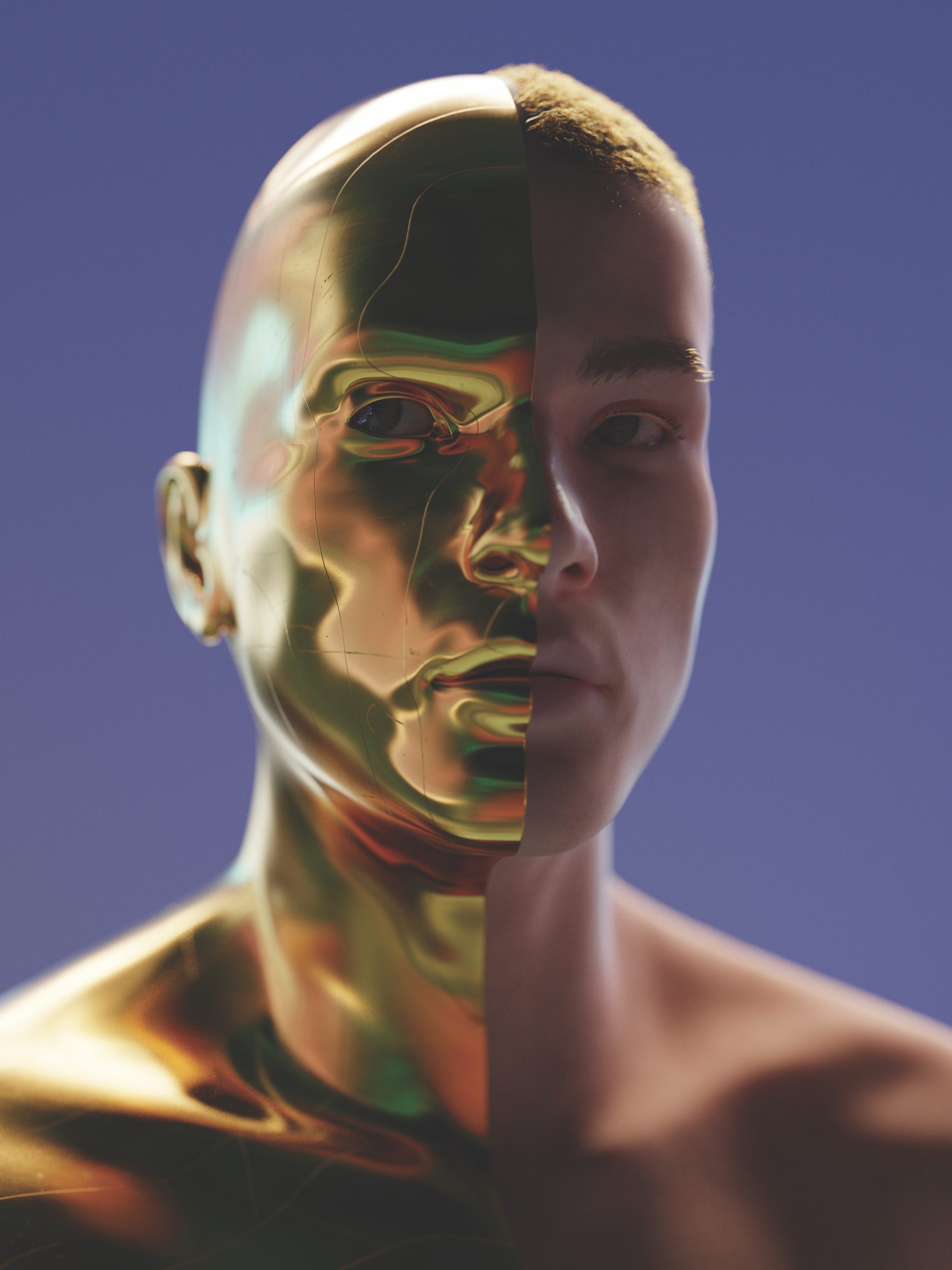

Serious concerns also surround scientists’ ambitions to make “more than human” individuals through implants, artificial intelligence-enabled exoskeletons, human-machine hybrids, human-animal hybrids, gene manipulation, neuro-robotics, micro-robotics, powerful drugs, electro-pharmaceuticals and biomimetic technologies. A swarm of practical and moral risks rises around attempts to “upgrade” the bodies of humans to develop augmented super-soldiers, military androids and cyborgs. The outlines of some of those quandaries were foreshadowed in ancient Greek times.

In myths about the legendary inventor Daedalus, the techno-wizard Medea and the super-watcher Argus, we find the earliest records of how the Greeks imagined it might be possible to augment human powers. Daedalus was a brilliant craftsman who famously fabricated wings for himself and his son Icarus to escape from King Minos’s labyrinth prison. Daedalus layered real feathers to make wings patterned on birds’ pinions. His replica wings were successful — both men achieved flight, but at a terrible cost. Icarus plunged to his death, in an accident anticipated by his father, who had warned his son not to fly too high.

In the epic story of Jason and the Argonauts, the cunning sorceress Medea devised ways to help Jason defend himself against superior deadly forces and overcome a series of obstacles to win the prized golden fleece. The first impossible task was to yoke a pair of fire-breathing, bronze bulls forged for King Aeetes by Hephaestus, the god of invention. Aeetes commanded Jason to plow a field with the brazen bulls and plant a helmet-full of dragon’s teeth. The king was confident that even if Jason somehow managed to avoid being burned to death and planted the teeth, he would be slain by the unstoppable automaton warriors that would spring up from the sown dragon teeth.

In search of ultra-powerful “pharmaka” (drugs) for Jason, Medea trekked to the high Caucasus Mountains, to the rocky crag where Zeus had chained Prometheus as punishment for stealing fire. Medea knew that a rare flowering plant grew in the soil wherever precious ichor dripped from Prometheus’s side as it was ravaged by the eagle. When cut, the strange plant’s fleshy roots oozed a black sap containing the essence of the immortal titan’s ichor. Ichor was the life-fluid of the immortal gods. Medea collected the sap and compounded a potent drug known as “Promethean.” The effects of the ichor mixture were spectacular but lasted only a single day.

The ichor drug gave the passive and scrawny Jason incredible courage and stamina. As Medea promised, he suddenly sensed “terrifying powers entering his body.” He felt “unbounded valor and great might like that of the immortal gods.” His arms twitched and flexed, his hands clenching at his sides. “Like a warhorse eager for battle,” Jason “exulted in the superhuman strength of his limbs.” As the ichor mixture coursed through his body, Jason “strode and leaped about, brandishing his spear and roaring like a wild beast.” Medea’s special Promethean drug transformed Jason into the Hulk. It gave him souped-up physical aggression and mental fortitude to successfully wrangle the unnatural bulls and withstand their searing breath long enough to complete the mission.

“These myths represent some of the earliest science fiction, and where imagination leads, innovation follows.”

The effects of the imaginary potion on Jason bring to mind the effects of synthetic psychoactive stimulants. There are reports of street drugs chemically related to but much stronger than cathinone from khat plants that can cause users to feel that they have superhuman strength and goad them into ferocious acts. Meanwhile, military pharmacologists are keen to develop complex human-enhancement concoctions that could supercharge soldiers mentally and physically, making them behave much like Jason under the influence of the Promethean ichor. Military-scientific projects seek drugs and neuro-technological brain interventions that would allow troops to exceed normal aggression, feel no pain, erase negative thoughts, override moral qualms about torture or killing, and obliterate memories of wartime violence or atrocities. The Pentagon’s scientists are also seeking neuro-pharmacological technologies to allow troops to go forego sleep.

These pursuits have historical echoes: in Homer’s epic poem about the survivors of the decade-long Trojan War, Helen of Troy mixed an elixir called nepenthe and gave it to the shell-shocked veterans to dispel their lingering rage, grief and traumatic memories of the battles and atrocities. There’s also the myth of Io, a young woman whom the goddess Hera sought to protect from being raped by Zeus. Hera deployed a giant android named Argus that possessed multiple eyes that never closed. In some ancient texts, Argus was called Panoptes (“all-seeing”). Argus Panoptes could watch in all directions with his many eyes. Hera bestowed two more enhancements on Argus: perpetual physical strength without normal fatigue and eternal vigilance. He never slept.

The English philosopher Jeremy Bentham, who died in the 1830s, designed a building called the panopticon to be used in prisons and other institutions, and he named the design after the hyper-vigilant watcher that could observe from all angles. The myth of Argus Panoptes also prefigures the proliferation of surveillance cameras and body cameras so ubiquitous in the modern world. It is no surprise that numerous security providers operate under the name Argus or Argos.

The human enhancement technologies sought by military scientists to allow soldiers to go long periods without sleep and still remain vigilant and able to carry out their duties ignores the still-mysterious necessity for sleep for human wellbeing. Notably, the myth did not end well for Argus, whose super-abilities were “hacked” by Zeus. Zeus sent his messenger Hermes to slay Argus. Hermes closed down each of the eyes with a secret code so that he could smash the sleeping giant’s head with a stone.

Human Enhancements In History

Replacement limbs and bionic body parts — the melding of human and machine — also have deep roots in mythology. In Celtic mythology, for example, King Nuada of the Silver Hand had an arm fashioned by the inventor god Dian Cecht. The Norse goddess Freyja was imagined as a kind of “organic cyborg” whose body combined both flesh and metal. In Hindu epic traditions, the heroine Vishpala lost a leg in battle and Vadhrimati lost hands, which the gods replaced with iron and gold replicas. In classical Greek myth, the inventor god Hephaestus made an ivory scapula to replace the missing shoulder blade of the hero Pelops.

The earliest historical record of a prosthetic body part was reported in the fifth century B.C.E. by the Greek historian Herodotus. Hegesistratus, a Greek soldier, lost part of his foot under torture by the Spartans. Hegesistratus managed to escape and had a wooden replacement foot made. He went on to fight in the Battle of Plataea on the Persian side because of his hatred for the Spartans. Another historical example was recounted by Pliny, who wrote how M. Sergius Silus, a Roman veteran of the Second Punic War against Carthage, wore an iron hand to replace the one he lost in battle.

Archaeological discoveries have unearthed surprisingly early evidence of artificial limbs and other body parts, some of them aesthetic and others functional. A skull from a site in France dated to 3000 B.C.E., for example, sported a false ear carved from a shell. Some of the most ancient prosthetic devices are quite sophisticated. In about 700 B.C.E., a highly skilled artisan who clearly understood the biomechanics of walking made a finely carved artificial toe for a woman. Archaeologists who discovered her mummy in 1997 near Luxor, Egypt, reported that the replacement toe not only appeared realistic but was tailor-made for her foot and even shows evidence of refittings. It was constructed in three sections of wood and leather, with a hinge for flexibility. Worn barefoot or with sandals, the woman’s prosthetic toe likely allowed relatively comfortable mobility.

An intriguing bionic eye was discovered by archaeologists in the ancient Burnt City site in Iran. The meticulously realistic artificial eyeball was embedded in the left eye socket of a woman who lived about 4,800 years ago. The anatomical details are amazingly true to nature, with a convex surface, cornea, pupil and an interior with extremely fine golden wires to mimic the capillary network inside the eye. It was the disquieting almost-real quality of 20th-century prosthetics that inspired the robotics engineer Masahiro Mori to describe in 1970 the eerie sensation known as the “uncanny valley” — the strange gulf in understanding a human-like object.

Metal body armor was another kind of early artificial human enhancement. Bronze armor was designed to make warriors’ bodies less vulnerable to weapons, of course. But what stands out about the bronze armor of classical antiquity is its form. The main piece of Greek hoplite armor, the cuirass or chest plate, was molded to look like the idealized male physique cast in bronze. Notably, the first robot ever described in Greek mythology (around 700 B.C.E.) was Talos, a giant android automaton that was constructed entirely of bronze. Ancient vase painters of the fifth century B.C.E. depicted Talos’s bronze body in the same way — using a yellowish-white color and indicating seams and rivets — that they used to portray the bronze chest armor of hoplite soldiers.

“Anatomical” bronze chest armor, also called “heroic” or “muscle” armor, first appeared in archaic Greece (seventh century B.C.E.) and became widespread by the fifth century B.C.E. The bronze cuirass was cast in two pieces, front and back, and attached by leather straps. Skilled smiths hammered the cuirass to fit over a man’s upper body, with realistic details in relief to mimic the naked torso of a superhero, with nipples, navel and impressively sculpted pectoral and abdominal muscles resembling those of the mythic strongman Heracles. The greaves (bronze leg armor) were also shaped to delineate well-defined shin and calf muscles.

“Sophocles cautioned that this same bold ingenuity ‘sometimes leads to good but sometimes to evil.’”

A Greek hoplite in bronze chest and leg armor was essentially wearing an exoskeleton that replicated the outer appearance of a nude, heroic statue. The muscle-bound bronze chest plate and greaves transformed every soldier — no matter what his body type — into an idealized warrior, a living Talos, a man of bronze. An advancing, clanking phalanx of Greek hoplite soldiers clad in muscle armor would present the enemy with what appeared to be a wall of superhuman warriors.

Today, U.S. military scientists are reviving a highly advanced exoskeleton idea inspired by the mythic figure of the bronze automaton Talos. Designated by the acronym T.A.L.O.S. (Tactical Assault Light Operator Suit), the special suit is to be augmented with artificial intelligence software, sensors, and offensive and defensive weapons systems. The design even features multiple “eyes” like Argus, the all-seeing guardian of myth, or Lynceus, the look-out on Jason’s ship Argo, whose extraordinarily sharp eyes could see in the dark and penetrate walls, trees, skin, and the ground.

In the fifth century B.C.E., the tragic playwright Sophocles wrote that we humans are formidable, for no other creatures have the skill and daring to navigate the stormy seas, plow the earth, tame horses and oxen, hunt and fish, devise laws, make war and build and govern cities. What other creatures have the facilities of language and “wind-swift thought” of “all-resourceful” humans, “ceaselessly contriving ways to escape the forces of nature”? Humans’ skills and inventive arts, Sophocles continued, are what drive us to achieve wonders and allow us to surpass nature. Yet we need to be mindful, Sophocles cautioned, that this same bold ingenuity “sometimes leads to good but sometimes to evil.”

Parts of this essay are adapted from the author’s recent book, “Gods and Robots: Myths, Machines and Ancient Dreams of Technology.”