Kathleen Miles is the executive editor and cofounder of Noema Magazine. She can be reached on Twitter at @mileskathleen.

A group of faculty and students at a small college want to cap the president’s pay based on what the janitors earn.

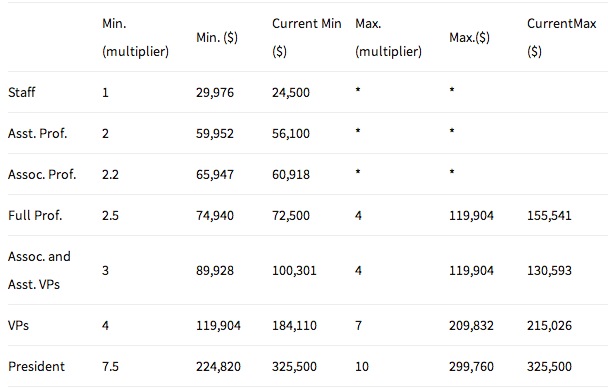

About a dozen faculty members and 30 students at St. Mary’s College, a public school in Maryland, have proposed a plan to limit the salary of the highest-paid employee to 10 times that of the lowest-paid employee.

The proposal recommends first raising the lowest yearly salary from $24,500 to $30,000, which is 130 percent of the federal poverty level for a family of four. A 1:10 pay ratio would then cap the president’s salary at 10 times $30,000, or $300,000 — $25,000 less than what the president currently makes. The activists used information on salary available only in paper form at the school’s library to find out what various workers on campus make, they said.

The individuals who crafted the proposal collected anonymous statements from some the college’s lowest-paid employees, including security officers, housekeepers and grounds crew members, who revealed that they rely on food stamps, WIC, heating assistance and other public assistance. One worker said she can’t afford and therefore skips needed medications and medical appointments; another said she has to borrow money to send her children to school field trips.

“I have to work overtime every week, had to let some of my bills go [unpaid] like my house phone, cable, and cut back on my heating, food, water, and my gas bill,” one worker wrote. “Sometimes I need to borrow money from friends, family, and by the time I get my pay check, I’m broke again.”

The proposal is expected to be discussed at the college faculty senate meeting Thursday. In order to be implemented, the faculty senate will need to pass it along to the board of trustees, which will need to approve it. The board’s chair and CEO declined to comment to HuffPost.

St. Mary’s isn’t the only institution facing a proposal to cap its highest earner’s pay. In California, nurses are collecting signatures for a ballot measure that would cap nonprofit hospital CEO pay at $450,000 a year, just over what President Barack Obama makes. In Massachusetts, nurses submitted to the legislature an initiative that would fine any hospital, even for-profit, that pays its CEO more than 100 times the hospital’s lowest-paid employee.

In Europe, the EU has introduced caps on bankers’ bonuses. France has imposed limits on CEO-to-worker pay ratios at state-owned firms. Switzerland considered capping executive salaries at 12 times the company’s lowest wage.

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission recently proposed requiring companies to annually disclose their CEO-to-median worker pay ratio, as a part of the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act. Some U.S. companies already either disclose their pay ratio or also cap it, including Whole Foods, NorthWestern Corp. and the Bank of South Carolina (where the CEO received four times its median pay of $48,000 in 2012).

St. Mary’s pay ratio was 1:13 for the 2012-2013 year, according to the pay cap campaign site — far more equitable than corporate America. Among America’s major companies, the average pay ratio is a whopping 1:204 — up 1,000% since 1950, when it was 1:20, according to Bloomberg data. An AFL-CIO report last year found that the ratio is even greater at 1:354.

But at college campuses like St. Mary’s, two storms are converging. First, like corporate CEOs, college presidents’ salaries have shot up. A total of 180 college presidents more than $500,000 in 2011, compared to 50 in 2004; even at public colleges, the median president pay was $441,000, according to a Chronicle of Higher Education analysis. Second, college tuition and fees in the U.S. have gone up 1,120 percent since 1978, a Bloomberg analysis found, leaving college graduates with an average of $26,600 in student loan debt.

Both of these storms shake the core values of colleges that ascribe to the ideals of social responsibility and accessibility, especially public, liberal arts schools like St. Mary’s.

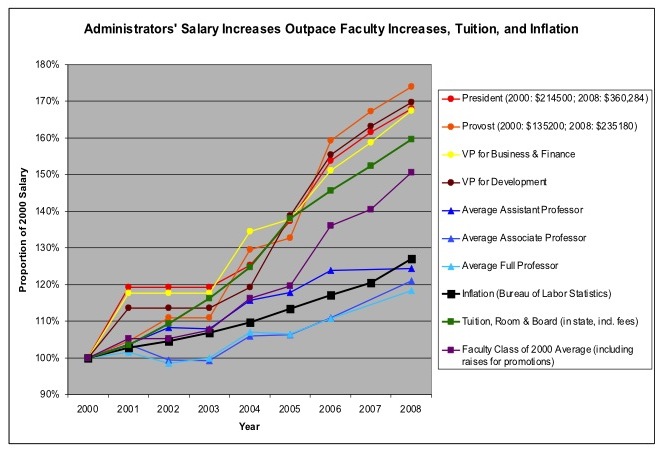

At St. Mary’s, the total salaries of the president and vice presidents have risen 91 percent since 2000, according to the pay cap campaign. And student tuition has risen about 60 percent since 2000. In contrast, St. Mary’s lowest-paid employees have had their salaries increase 56 percent over the same time period, the activists say, and associate and full professor pay has actually increased at rates that are lower than inflation — 29 and 22 percent, respectively.

St. Mary’s Interim President Ian Newbould said that the college does not have a position on the pay cap proposal because wages for staff are negotiated by a union. “I understand the thinking behind [the proposal],” Newbould said. “But it would be improper for the college administration to be talking about these issues outside of union negotiations.” He said that the board will consider the proposal when it is brought to them. Advocates of the proposal say they are in communication with union representatives and are open to their concerns.

This chart by the advocates shows how tuition and executive pay have increased more quickly than salaries for lower earners:

The college has taken some measures since 2008 to curb administrators’ pay, but the pay cap proponents say it isn’t enough.

The expectation is that, by inhibiting rapid growth of executive pay, the pay cap would save money in the long-term that could be used to lower tuition, according to David Kung, a math professor at St. Mary’s and one of the campaigners. The proposal comes months after President Obama challenged colleges to develop innovative ways to make their schools more affordable. In the same speech, Obama proposed ranking institutions based on access, affordability and student debt.

Here’s how the 1:10 pay cap ratio would increase the lowest salary, lower the highest and incrementally spread out those in the middle:

Some have argued back against the proposal, saying that St. Mary’s should follow the free market. If it doesn’t, they say, the college will fail to attract talented executives. The school is currently in the midst of looking for a new president right now. Opponents also say that because higher pay at the bottom costs more, the college could be forced to cut jobs or contract out lower-paid positions instead of hiring in-house, and they argue current administrators could leave for jobs at colleges without caps.

“Employers base pay according to workers’ productivity. This sort of pay cap proposal attempts to redistribute wages from the most productive employees to less productive employees,” said James Sherk, senior policy analyst at the Heritage Foundation. “In doing so it will severely distort hiring decisions.”

The campaigners counter that exorbitant pay is no guarantee of excellence and that they want a president who values equity and is even willing to take a pay cut for it.

“We’re deeply attached to our public identity,” said Sandy Ganzell, math and computer professor at St. Mary’s and one of the campaigners. “There’s no such thing as the best college president out there; there’s the best president for St. Mary’s … and that’s the person who believes in our mission.”

The campaign suggests promoting from within instead of plucking administrators from other schools with the lure of high pay. “This was the norm in higher education for many years,” the campaign’s site reads. “A professor who understood the institution and wanted to be an administrator rose through the ranks and eventually took over as president.” Competing for talent with other institutions is unwise, campaigners say, since many of St. Mary’s competitors are better-funded, private colleges that can offer more money.

It is unclear if St. Mary’s roughly 30-member board of trustees will approve the proposal. The earliest it could be implemented is in the 2015-1016 school year.

In the meantime, Robin Bates, an English professor at St. Mary’s and one of the campaigners, said their proposal is gaining attention at other college campuses.

“We’ve gotten emails from people around the country who are very interested in this. We’re sharing info with faculty members at other schools,” he said. “It would be wonderful to see this exported elsewhere.”