Nathan Gardels is the editor-in-chief of Noema Magazine. He is also the co-founder of and a senior adviser to the Berggruen Institute.

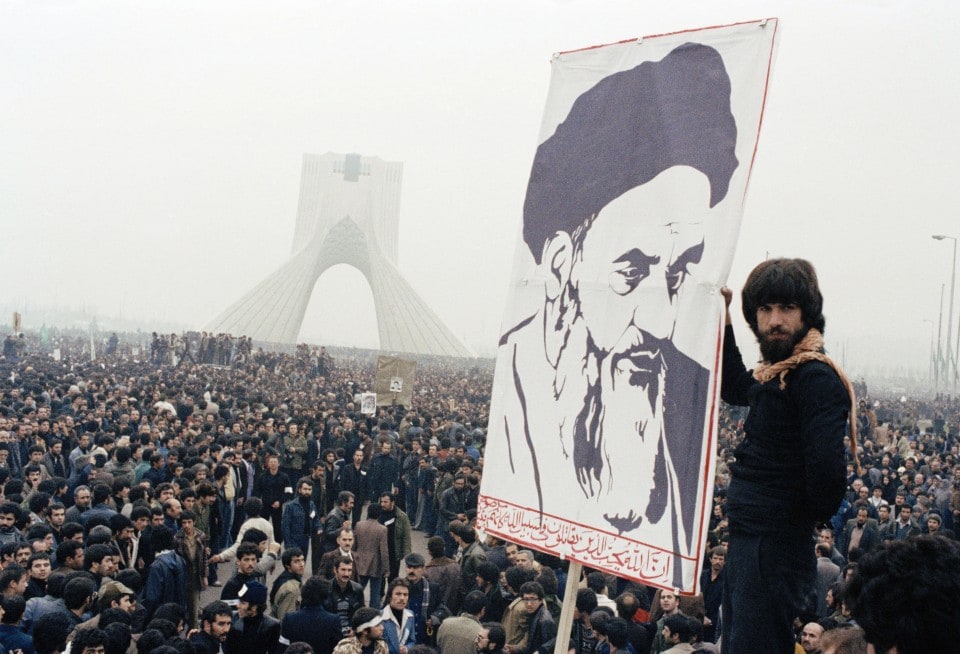

Abolhassan Bani-Sadr was the first president of the Islamic Republic of Iran after the 1979 revolution. When the hardliners of the clergy, aligned with Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, pushed Bani-Sadr from power through a coup in 1981, he fled to France, where he continues to live in exile. He spoke with WorldPost editor in chief Nathan Gardels to mark the 40th anniversary of the Iranian Revolution.

WorldPost: Let’s go back to the beginning. What hope inspired you to help lead the Iranian Revolution 40 years ago?

Abolhassan Bani-Sadr: In 1962, I delivered a speech in a debate among Iranian students titled “Revolution is the gift of the young generation to ancient Iran.” I was advocating for such a revolution, a spontaneous mass uprising.

Recalling the 1953 coup by Britain and the United States against the democratically elected prime minister, Mohammad Mosaddegh, I came to the conclusion that Iran was being held down by its consumer-oriented economy based on exporting crude oil and importing goods from the West — a closed-circuit relationship dominated by the shah’s regime inside and Western interests outside. The only way the country could develop would be through an open social system, in which relations are not regulated by force and domination but by rights guaranteed and exercised by the people themselves. It was on this basis that we were able to build a consensus to challenge the shah and his puppet relations with the West.

When Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini came to Paris years later in 1978, during his nearly 15-year exile from Iran, he accepted this approach of a movement for change. Our hope then was that if the clergy committed itself to these principles, there would be no obstacles to their implementation once the shah was forced out. However, Khomeini began to alter and violate the principles of a rights-oriented system after arriving in Iran when the shah fled. Contrary to our expectations and their pledges, the clergy turned against the very ideas that drove the shah from power.

WorldPost: If you knew then what you know now, how would you have acted differently as a revolutionary leader?

Bani-Sadr: The better question would be: “If a revolution could take place at will, when would be the best time for it to happen?”

From the outset, the Iranian revolution did not lay the proper groundwork for a rights-oriented state before overthrowing the monarchy. One of our key ideas back then was to establish councils at every layer of society, from villages to towns and cities, and through them a “council of revolution” that would embrace a rights-orientated system from the bottom up.

Though Khomeini had promised to implement this approach when he was exiled in Paris, after his return to Iran in 1979, he instead sought to establish authority by reconstructing despotism through theocratic rule. We now know that he had plotted that in secret while still in Paris. If I had known then what I know now, I would have done my utmost to expose this plan in order to make it hard or impossible to implement.

WorldPost: Revolutions go through many stages. Four decades on, where do things stand now?

Bani-Sadr: It is obvious that revolution is the beginning of a transformation, not the end of it. Iranians are one of the only people in the world to have launched three major uprisings and revolutions for democracy, independence and freedom in a single century: the Constitutional Revolution in 1905, the nationalization of the oil industry in 1951 and the 1979 revolution.

This had significant structural consequences. Historically, despotism in Iran had been based on four pillars: politically, the monarchy and its armed forces; economically, the big landowners and the bazaar economy; culturally, the clergy; and externally, relations with domineering foreign powers. As a result of these successive revolutions, all the internal pillars except the clergy have been removed.

Today, at long last, the clergy’s legitimacy is in drastic decline. The majority of the clergy oppose and have distanced themselves from the ideology of the ruling regime. To maintain its fragile hold on power, the ruling clergy seeks to foment and sustain crises with foreign powers. The creation of such crises has become intrinsic to the nature of the Iranian regime since the days of Khomeini.

Yet we need to see this as a tango in which each party needs a cooperative partner. At the moment, President Trump is playing the role of that partner. Not understanding this history, he is only bolstering the power of the ruling clergy, which would otherwise weaken to the point that popular discontent could remove it from power.

WorldPost: Can the original aims of the revolution still succeed after all these years? What conditions are necessary to make that possible?

Bani-Sadr: In one sense, Iranians are lucky, as they are always starting new experiments. However, they are also unlucky because they come under attack from external powers who seek to make them regret what they have done.

Despotic structures from within combined with the assistance of foreign powers from without has created big obstacles to a homegrown republic, frustrating the aspirations of most Iranians. They are the evil twins that reinforce each other.

In Iran, the people will do their part and one day will bring the revolution to its logical conclusion — a “republic of citizens.” If the West really wanted to help realize the original promise of 1979, the wisest thing to do would be to find ways to decrease confrontation with the regime instead of finding ways to increase it.

In the present moment, Trump is the co-conspirator with Khomeini’s heirs in keeping the Iranian people down.

This was produced by The WorldPost, a partnership of the Berggruen Institute and The Washington Post.