ANTAKYA, Turkey — When mass anti-government protests erupted in Syria’s largest city of Aleppo in the spring of 2011, Abu Mohamed, then a 22-year-old English teacher fresh out of college, eagerly joined in to demand something he had long dreamed of: freedom.

Three and a half years later, in the midst of a bloody civil war that has claimed well over 190,000 lives and torn apart the country, Abu Mohamed doesn’t support the more moderate groups fighting the Syrian regime. He instead supports a hardline jihadist group that has quickly gained a reputation as one of the world’s most powerful and violent terrorist organizations — the Islamic State.

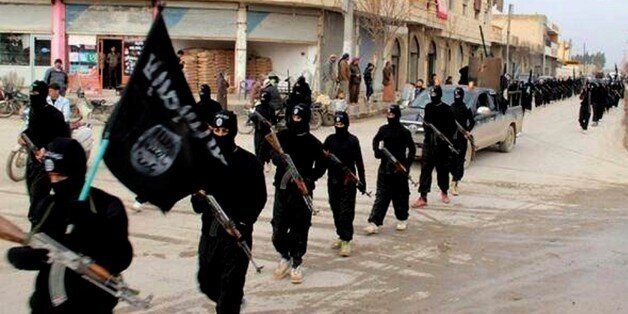

Over the past year, the extremist Sunni Muslim group has gained ground in northern Syria, and more recently, in large swaths of northern and western Iraq. The fighters, many of whom are foreigners who have flocked to Syria, claim to want to establish an Islamic Caliphate.

The group has proudly posted videos of its members beheading American journalists, and its fighters have carried out mass executions. In some cases, they have given religious minorities in the territory they control a choice to convert or die. The United Nations has warned that the Islamic State is committing crimes against humanity.

But the young schoolteacher barely resembles the often brutal, gun-wielding, Sharia-law-enforcing fighters who now patrol his town of Maskanah, roughly 60 miles from Aleppo in the country’s north.

Before the war, Abu Mohamed — a name he gives to protect his real identity — studied liberal arts alongside uncovered women. He taught in mixed-gender classrooms. He danced and joked. He says he was not committed to Islam.

But now, everything has changed. His country resembles nothing of the Syria he once knew. When the Syrian regime pulled out of Maskanah and the surrounding area around mid-2012, leaving behind destruction and chaos, rebels who were aligned with the loosely Western-backed Free Syrian Army seized control. Abu Mohamed said these rebels, who have long struggled with infighting and a severe lack of funds, failed to instill real stability in his town. According to him, looting was rampant, salaries were slashed, and oil, food and other essential goods were scarce and grossly inflated in price. Abu Mohamed’s battle cry for freedom and justice morphed into one for survival and security.

And then about a year ago, according to reports, extremist fighters who are part of what is now called the Islamic State assumed power in Maskanah, pushing out more moderate rebels. At first, Abu Mohamed was unsure of how he felt about the group, whose reputation preceded it. But it didn’t take long to win his support.

“Security is good now,” he said, speaking openly with The WorldPost over the phone. “There’s no robbing, no stealing. The price of oil is good. Facilities and schools are running. Electricity is back.”

While the Islamic State is known for using fear as a weapon of war, in some places, it’s winning hearts and minds by instilling something hard to find in Syria nowadays: a semblance of stability. In Islamic State-controlled areas of northern Syria, the group is laying groundwork for a local government, keeping prices down and even controlling traffic. Through hefty foreign donations, oil smuggling, taking hostages and demanding huge ransoms, extortion and other means, the group’s funding has swelled, making the Islamic State one of the richest terrorist groups in the world.

“The Islamic State is the most organized and the most funded,” Abu Mohamed said. “They’re made of money.”

The young schoolteacher responsible for 30 elementary school students said he made the equivalent of $50 per month under the Assad regime, made no money when moderate rebels controlled his town, and now makes $150 per month. According to him, he’s sometimes paid in oil now. It’s a salary he can live on.

But with Islamic State control and new opportunity comes a slew of changes. Abu Mohamed said teachers in Maskanah now must pass a test on Islamic knowledge before being allowed to teach. And girls and boys past elementary-school age can no longer learn together in the same classrooms.

It’s in one of these mixed-gender classrooms in Aleppo that before the war, Abu Mohamed met the woman who would later become his fiancee. There, university men and women attended classes together. Some women dressed conservatively and covered their hair, while others wore tight jeans and let their hair down.

But now, in areas under the control of the Islamic State, women have to cloak their bodies in loose black fabric. While his fiancee used to cover her hair for tradition’s sake and not because she was particularly devout, she now must wear a niqab, a black cloth that completely covers her face. Smoking and drinking is strictly prohibited. And those who disobey Islamic State-enforced laws are punished, sometimes with a fine or forced labor, but other times with violence, public shaming or even death. In late February, the Sunni extremists in Maskanah live-tweeted the amputation of the hand of a man who they deemed a thief.

Abu Mohamed said he supports the Islamic State punishing civilians within reason, if it means there is rule of law. He said he also has seen quite a few executions of Syrian soldiers in Maskanah, reportedly beheaded in public by Islamic State fighters. While he firmly opposes the execution of civilians, he supports the killing of regime fighters, even if they’re unarmed captives. He’s no stranger to indiscriminate airstrikes from the regime of Bashar Assad targeting civilians.

“They were killing Syrians,” he explained.

Abu Mohamed said neighbors, friends and other locals either linked to the regime or to more moderate rebel forces have fled Maskanah. He regularly gets into arguments with friends who say the Islamic State is terrorizing people. But he’s holding out hope that somehow, someday, more moderate and cash-strapped fighters like those supported by the West will join the Islamic State to form an inclusive, well-funded front against the Syrian regime.

Despite the Islamic State’s brutal reputation and its unapologetic use of violence, Abu Mohamed is convinced that the group doesn’t persecute religious minorities or people who do not abide by their brand of Sunni Islam. “They just try to convince them of Islam,” Abu Mohamed said defensively, without elaboration. Iraqi Christians and other minorities interviewed by The WorldPost who have recently been persecuted by the Islamic State tell a very different story.

Abu Mohamed himself has become far more religious, saying that the Islamic State has reminded him of what it means to be Muslim (though many Muslims around the world say the group does not represent Islam in any way).

“We’ve found the soul of it,” he said proudly, referring to Islam.

Abu Mohamed insists that the beheadings of American journalists James Foley and Steven Sotloff are the work of militants pretending to be the Islamic State. His friends fighting with the extremist group told him so, he said.

While he supports the hardline group and its strict rules — and the stability they bring — Abu Mohamed says he disagrees with their stated end goal. He just wants the regime to fall, not the establishment of an Islamic Caliphate.

And this is where his support gets complicated. While some of his Syrian friends have joined the ranks of the Islamic State, many of the fighters who walk the streets and control Maskanah, he says, are foreigners from places like North Africa, Saudi Arabia and Europe.

“I welcome them to fight the regime,” he said. “And then leave. The most important thing is to defeat the regime, but then go back home.”

Abu Mohamed says he wouldn’t mind if the Islamic State stayed forever in Syria — as long as those in power are Syrian.

“I want to be responsible for my own country,” he said.

A Syrian journalist contributed reporting to this story from Antakya, Turkey.